ARS ELECTRONICA ARCHIVE - PRIX

Der Prix Ars Electronica Showcase ist eine Sammlung, innerhalb derer die Einreichungen der KünstlerInnen zum Prix seit 1987 durchsucht und gesichtet werden können. Zu den Gewinnerprojekten liegen umfangreiche Informationen und audiovisuelle Medien vor. ALLE weiteren Einreichungen sind mit den Basisdaten in Listenform recherchierbar.

Jeffrey Shaw

Jeffrey Shaw

Original: conFiguring the CAVE 1997.jpg | 1535 * 1181px | 607.2 KB | conFiguring the CAVE, 1997 | © ICC Tokyo

Original: GOLDEN CALF 1994.jpg | 2568 * 1927px | 1.5 MB | Golden Calf, 1994 | © Jeffrey Shaw

Original: JeffreyShaw_photo.jpg | 2746 * 3120px | 6.0 MB | Jeffrey Shaw

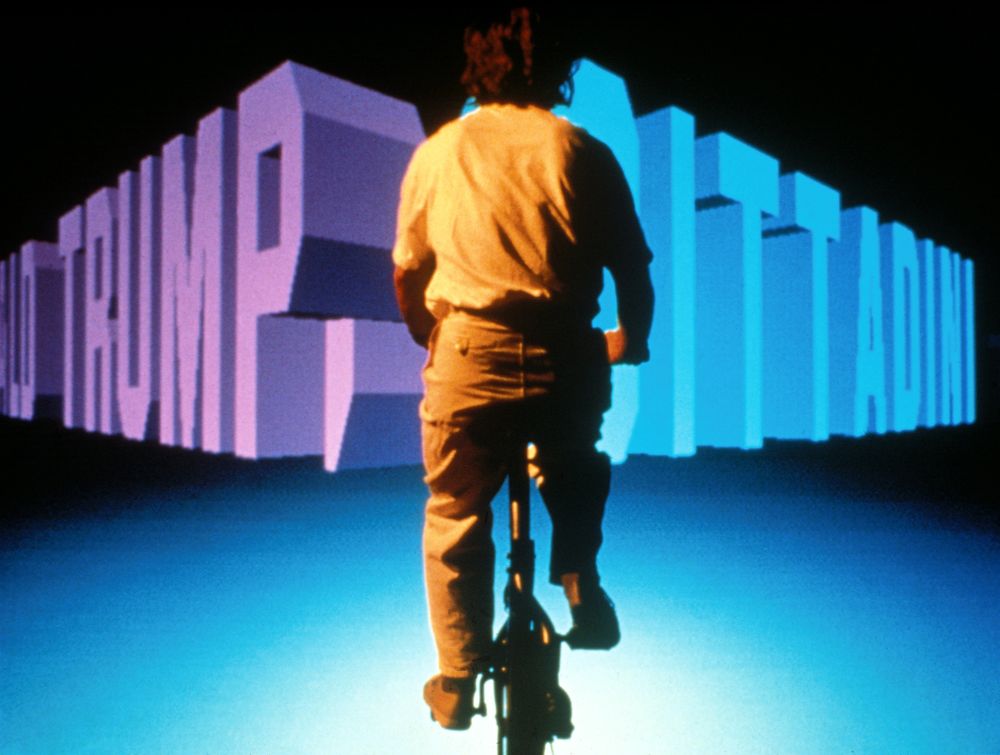

Original: LEGIBLE CITY 1989.jpg | 3089 * 2335px | 1.5 MB | Legible City, 1989 | © Jeffrey Shaw

Original: T_VISIONARIUM 2006.jpg | 4992 * 3320px | 2.7 MB | T_Visionarium, 2006 | © UNSW iCinema

Original: WATERWALK 1968.jpg | 2057 * 1542px | 865.8 KB | Waterwalk, 1968 | © Pieter Boersma

Jeffrey Shaw—Pioneering the New Media Experience

Anne-Marie Duguet

Jeffrey Shaw is a pioneer in the field of new media in numerous respects. The breadth of his influence is due not only to the experimental and radically anticipatory character of what he has produced, it is also the outcome of the context of the research work he has carried out since the early 1990s at several institutions. Equally important were the positions he held at ZKM—Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe and the UNSW iCinema (Sydney) and now holds at the CityU School of Creative Media in Hong Kong. He was thus able to conceive ambitious projects that did not have to conform to either the exigencies of a market or the criteria of legitimation of contemporary art, and were also not subject to economic constraints. His initiatives nurtured an attitude towards creativity and research that enabled him to encounter technology in a way that was free of prejudice and yet still permitted him to maintain a critical eye with respect to the utilization of this technology and its limitations. It is also to this formidable dynamism that one must pay tribute today.

The singularity of Jeffrey Shaw’s oeuvre already manifested itself in his first animated film and continues to do so today in his virtual environments—namely, the constant dialectic between the explicit appropriation of languages, techniques and models of representation derived from many different cultural traditions and the exploration of those new territories that technologies have opened up to him.

His first works—produced in the context of the intellectual, cultural and political ferment of the 1960s and 70s—manifest the principle paradigm shifts of contemporary art: refocusing attention towards the dispositif of representation and the prevailing conditions within which this representation is experienced; the involvement of the spectator in accordance with multiple perceptual, mental and behavioral modalities; the insistence on the process and the context of the work; the consideration given to history and memory; the interest in the heterogeneity of language; the collaboration among artists working in different disciplines; and, finally, the experimentation with alternative settings for art.

What emerged in particular over the course of these years is an artistic personality that gradually garnered recognition as an inventor of systems as well as a producer of specific technical and conceptual constellations that would later be referred to as dispositifs.

There is neither representation nor experience outside of a dispositif. In fact, it is the very condition of their possibility. Artistic installations, above all those of experimental cinema and video, have had the task of analyzing what constitutes the foundations of the dominant mode of representation since the Renaissance. It is not cinema or painting or the photo that is submitted to a meticulous re-examination but rather it is the entire ensemble of mythic and non-mythic dispositifs that is brought into consideration, from Plato’s cave to Brunelleschi’s tavoletta, from the camera obscura to Dürer’s perspectival gateway, from panoramas to contemporary surveillance systems. The entire history of representations is rehearsed every time in these theaters of seeing, whose heuristic function thus becomes quite clear.

This critical, analytical and reflexive dimension of the installation has been essential to Jeffrey Shaw’s oeuvre. In recombining various elements of the cinematic dispositif so as to allow unique configurations to develop out of them, as well as by coupling that dispositif of representation with other ones, the artist has repeatedly exposed the limits of the standard regulations of traditional cinema. Multiple screens, environmental projections, interactive scenes—the image is exceeded in every one of its dimensions, even at the level of its fullest and most complete nature.

The question of time has heavily impinged on artistic theory and practice since the 1960s. It has emerged not only as a recurrent theme but also as a constituent parameter of the very nature of an artwork. Performances, environments, events, installations have an exploratory duration, they are eminently contingent, closely tied to the specificity of a site or a context, and often dependent on the direct intervention of the audience. They necessarily incorporate chance and accident.

With these early works, Shaw began to conceive of an artwork as an “event structure” (a notion developed by John Latham),I a field of complex interactions composed of simultaneous events, each having its own duration (a performance act, the running time of a film, various physical phenomena).

Shaw then appropriated highly diverse techniques and elements, preferably fluid, evanescent, malleable, and inconsistent: water, fire, air, neon, polyethylene, pneumatic devices, pyrotechnics, films, photos, lasers etc. What counted was their ability “to physically embody the immaterial,” which still remains an issue and above all an interrogation at the heart of Shaw’s research.

Exceeding Architecture / Expanding Cinema

By adopting the principle of inflatable structures, Shaw exceeded the limits of architecture and proposed a soft architecture that is transformable, mobile, ephemeral and receptive to intermediate states. This concept was later developed further in Utopia Triumphans (2002). From a vocabulary of architectonic forms that pervade one another and protrude into a virtual space, a structure is permanently auto-generated in accordance with certain algorithms.

The critical and highly provocative approach of the Eventstructure Research Group (with whom Shaw produced his first pieces in 1967) entailed not only conceiving architecture as spatially fluid but also making it practicable. Pyramids, pavilions and domes became playful spaces able to produce unusual sensations for all visitors.

Right from the start, Shaw’s artistic practice addressed a broad audience, not merely that of art galleries. The desire to avoid making art a separate activity, to connect it to everyday life, prompted him to seek out new exhibition contexts such as a street, a facade or a canal. Neon Wave Sculpture (1979) was a kinetic light sculpture placed high on the side wall of a building. A luminous wave traveled through the neon tubes, describing a programmed pattern that was determined according to the speed of the wind. The artwork was thus rendered “sensitive” to natural phenomena and was open to chance factors (a key parameter in Cage-influenced experimentation of the day) including public intervention.

One important aspect of such pieces is the often collective nature of their production. The early 1960s saw increasing collaboration between artists from different fields. The Experiments in Art and Technology group (E.A.T.) for instance, was designed to spur encounters between artists, technicians and scientists. Such cooperation stemmed not only from the very nature of pieces that entailed complex technical and computational systems requiring specific skills, but also from a conception of artistic practice as ongoing work, activity, process and experimentation that escape the control of a single artist. Art was no longer a question of a sole creator’s subjectivity. This attitude has been a driving force behind Jeffrey Shaw’s output; he has always collaborated with several programmers as well as with writers, composers, artists and art historians.II

As much as architecture, Shaw appropriated cinema to re-work its constituent principles. With his first installation, Emergence of Continuous Forms (1966), he inaugurates a series of “expanded cinema environments”, expanded in space by projecting his film onto a series of semi-transparent screens set up over the length of the gallery, as well as by the intervention of visitors who could modify one screen by inflating it.

The question of the screen—be it three-dimensional and borderless or a viewing window—has been central to Shaw’s thinking; he subjected it to a multitude of trials, steadily challenging its specific qualities: paper screens are torn, smoke screens dissipate etc. The image printed on the film strip is no longer the main center of interest, rather it is the uncertain status of the projected image, the image-in-formation. Film projection itself thus becomes a performance. Shaw declared, “all my works are a discourse, in one way or another, with the cinematic image, and with the possibility to violate the boundary of the cinematic frame—to allow the image to physically burst out towards the viewer, or allow the viewer to virtually enter the image.”III Two “performance events” produced in the Netherlands in 1967, Corpocinema and MovieMovie, sum up his exploration of this notion of expansion. The “corpocinematic concept” also meant giving body to film, endowing it with volume, the third dimension that it lacked.

lt was not the arrival of digital simulation and the resulting possibilities of specifically interactive modes that prompted Jeffrey Shaw to interrogate the relationship between spectator and artwork. His environments, events and installations, although the ones not employing computer technology, necessarily implied and defined procedures of involvement that went beyond simple levels of contemplation, identification or interpretation. What clearly emerged then was the idea of the audience’s responsibility, that its presence as well as a deliberate intervention was an integral part of the overall process.

A retrospective look raises one point of particular interest, namely the way in which Shaw immediately generated experimental fields and experiential “occasions” that involved the human body in playful, poetic actions, and that were, in a way, precursors to the perceptual situation now offered to travelers in virtual worlds. Impressions of immersion, floating and suspension were all effects engendered at the time by provocative concepts like Shaw’s “soft responsive architecture.” They belong to an initial group of experiments on the notion of environment as organic space.

Anticipating Augmented Reality

Well before the use of computers, Viewpoint (1975) provides a good example of Shaw’s systematic investigation into the nature of virtual images and of the potential of installations that he began to explore for exposing representational processes. This work powerfully inaugurated the total dependence between the image and its spectator, as in a mirror situation. An image was no longer given, could not pre-exist its actualization—here, its perception by a spectator. The point of view became the very site and condition of visibility. In several other pieces, such as The Golden Calf, The Virtual Museum or the series of Place, the construction of optical illusion was dependent on the perfect coincidence of the spot from where the photograph or video was shot, the source of the image projected (or displayed on a screen) and the position of the observer.

The radicalization of the process of virtualizing images inevitably led to the complete abolition of the screen. Thus right from the late 1970s Shaw began developing a “see-through virtual reality system” based on stereoscopic principles. His optical device (a forerunner of the head-mounted display HMD and BOOM) coupled a semi-transparent mirror with a computer screen onto which two wire-frame images of a cube were displayed. The spectator could observe the basic rotation of the cube projected onto the room, integrated with the other elements of the space. In this Virtual Projection Installation (1978) the original function of the “screen” had completely evolved toward a “viewing system” but it was henceforth in the hands of the spectator. With Points of View (1983), the image became an environment to be activated and transformed. Once the spectator enters the scene, representation lost its autonomy and become a theater of operations.

Virtual Totality and the Panoramic Impulse

For the interactive sculpture Inventer La Terre (1986), Shaw developed another viewing device comprising a small video monitor and a periscope installed in a column with an opening in the middle through which the spectator looked at the exhibition space. By rotating the column, the viewer selected various sites to explore within a virtual panorama; floating travelogue images of the selected site then appeared superimposed onto the exhibition space. Tales, signs and symbols taken from ancient times and cultures on various continents, expressed the multiplicity of representations of the world, constituting what Shaw calls a kind of “museum within the museum.” This work, meanwhile, crystallized a major notion within his own oeuvre, namely “virtual totality,” based on the twin principles of the viewing window and the panorama.

Since Diadrama (1974) devised for a theatrical stage, Shaw developed his work on environmental immersive projection through various dispositifs, based on a sphere or a cylinder, exploiting the model of the panorama. Place—A User’s Manual (1995) combines and reinterprets two key elements of the 19th-century panoramas: the circular screen and the central observation platform. The image is projected onto the screen from a small rotating platform where the visitor stands, providing a privileged point of observation. Since the image covers only one third of the screen, the observer can generate a total view of the panorama solely through time and a continuous sweep. The spectator’s memory and capacity for anticipation are required to complete the environment. The dialectic between global and fragmented view, already present in several of Shaw’s pieces, becomes all the more striking in Place—A User’s Manual insofar as total vision is precisely what the panorama promises. But while the viewer gains the control of exploration and the feeling of power it confers, he has to deal with a constant negotiation between manipulation and contemplation.

Cultural Heritage

The television screen of Revolution (1990), which fully assumed the metaphor of a “window on the world”, displayed the vast visual memory of revolutions since 1789. Visitors were invited to turn the wheel of history and access a series of images constituting humanity’s collective memory.

In more recent works Place—Hampi (2006) or Pure Land—Inside the Magao Grottoes at Dunhuang (2012), both in collaboration with Sarah Kenderline, Shaw pursues research on World Heritage sites by exploiting these two similar environmental systems: the panorama as re-worked in the Place series, and the AVIE,IV a stereoscopic interactive visualization and audio environment. With a cylinder twice as high as Place, it is the most immersive system conceived by Shaw, to be explored with polarizing glasses, which eliminate the distance to the scene and isolate the viewer from the actual environment. The realism of the experience is reinforced by the 1:1 scale of high-resolution photography and the surrounding sound system.

Photography fixes the memory of an architectural grouping. However, the myth escapes any capture and its “documentation” can only be the actualization of an imaginary representation. By activating the high-resolution panoramas of the archeological site of Vijayanagara in Hampi, one comes across beings that are not photographic but animated representations. Digital characters inhabit these spaces as “living” gods and mythical figures from the Ramayana, bringing to life an ancestral collective memory, evoking contemporary beliefs about the creation of the site.

Pure Land is another “theater of memory” in which the visitor can explore one painting of the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas with a device simulating a torch light, or a magnifying glass to look into details. Here 3D animations are also called on, giving poetic and historical information such as ritual dances or musical instruments of the time.

With this undeniable way of preserving an exceptional heritage two main issues are at stake. First, a methodological bet: getting back closer to the project of the historical panoramas with advanced technology, it provides a persuasive surrogate kinesthetic experience of a site, based on immersion and narrative to stimulate the imagination and desire for discovery. Secondly, the multi-layered interpretation of the site history and of its various cultural elements, this “augmented memory” resulting partly from reconstitutions, question the “document” as a given trace speaking by itself. As Michel Foucault stress in The Archaeology of Knowledge, the primary task of history now in relation to the document is: “to work on it from within and to develop it [...] trying to define within the documentary material itself unities, totalities, series, relations.”V

Discontinuity and Simultaneity in Narrative

Structures

Different forms of narrative are at work in most of Shaw’s installations: autonomous micro-narratives in Viewpoints which the spectator can access in no particular or predetermined order, or narrative lines to follow/read in the calculated streets and 3D architectural texts of Legible City. Parallel narrations respond to the multiplicity of points of view, often in the mode of a fragment, without links but with passages and with possible leaps from the one to the other. Meanings are largely produced by the spectator from a virtually discontinuous linearity. Beyond the text itself, it is the very conception of potential pathways—the manner in which the text/ image “happens”—that enables a reader to develop his/her own branching rhizomes.

The “theater of signs” of the first Shaw works has given place to scenes performed by actors as in Eavesdrop (2004) or The Infinite Line (2014) with the poet Edwin Tumboo. Nevertheless a very singular narrative engagement between users and virtual characters is at stake in UNMAKEABLELOVE (2008), in collaboration with Sarah Kenderline. Computer- generated human bodies VI perform, with a paradoxically autonomous obsessive behavior in a prison- like space. Inspired by The Lost Ones by Samuel Beckett, there is no text but a complex dispositif based on a surveillance system of the other and of the self simultaneously. The visitors, outside a hexagonal construction, the Re-Actor, referring to the model of the Kaiser panorama, peer into this virtual cage with probing torch lights replacing the windows of the Panopticon and surveillance cameras.

What makes Shaw’s approach so innovative does not so much lie in his exploration of some of the most advanced techniques available, as it does in his invention of interfaces. As the executor of transactions between the virtual and real, the interface is necessarily at the heart of his research. Inseparable from the whole dispositif, it is part of a whole web of metaphors. Shaw creates architectures/ interfaces that respond both together to the conceptual requirements of a particular project, and to the perceptual conditions of these new works that the virtual environments are, repeatedly, inventing other ways of seeing and experiencing a work.

The text includes excerpts from Anne-Marie Duguet’s essay published in: Duguet, A-M., Klotz, H., Weibel, P. (1997). Jeffrey Shaw—A User’s Manual: From Expanded Cinema to Virtual Reality, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

I John Latham, artist, taught film at Saint Martins School of Art, London, where Shaw studied in 1966.

II Collaborators include: software developers—Larry Abel, Gideon May, Adolf Mathias, Bernd Lintermann, Matt McGinity, Leith Chan; writers—Dirk Groeneveld, David Pledger; composers—Harry de Wit, Les Stuck, Paul Doornbusch, Torsten Belschner; artists—John Latham, Tjebbe van Tijen, Theo Botschuijver, Agnes Hegedues, Dennis Del Favero, Bernd Lintermann, Saburo Teshigawara, Peter Weibel, The Wooster Group, Jean Michel Bruyere, Sarah Kenderdine.

III Jeffrey Shaw in discussion with Ueno Toshiya: “We are Materialists, We Employ Science and Technology to Concretize the Virtual,” in Media Passage, ed. lnterCommunication Center, Tokyo, 1993, p. 53.

IV AVIE (Advanced Visualisation and Interaction Environment) collaboration Jeffrey Shaw, Dennis Del Favero, Matthew McGinity, Ardrian Hardjono, Volker Kuchelmeister. UNSW iCinema Centre, Sydney. AVIE is “a cylindrical silver projection screen 4 meters high and 10 meters in diameter. It has a set of 5 high-resolution digital video projectors that together project an active 3D 1000 x 8000 pixel stereoscopic picture over the entire 360-degree surface of the screen.” (cf www.epidemic.net)

V Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, Pantheon Books, New York, 1972, p.6-7 Trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith

VI “The obsessive behaviours of these inhabitants have been motion captured, computationally animated and then rendered in real-time using a game engine and ALife and algorithms.” (Shaw and Kenderline’s description)

Anne-Marie Duguet (FR) is Professor Emeritus at University of Paris1 Pantheon-Sorbonne. She is the author of books such as Vidéo, la mémoire au poing (1981), Jean-Christophe Averty (1991), Déjouer l’image. Créations électroniques et numériques (2002). Art critic and curator: Jean-Christophe Averty (Espace Electra, Paris 1991); Thierry Kuntzel. (Jeu de Paume, Paris, 1993); Smile Machines (Akademie der Kunst, Berlin, 2006); co-curator of Artifices Biennale, Saint-Denis, (1994, 1996). Director of the multimedia series anarchive (Muntadas, Snow, Kuntzel, Otth, Nakaya, Fujihata).

Photos

1 The Legible City, 1989-91, Artec, Nagoya, Japan

Co-author: Dirk Groeneveld; Application software: Gideon May; Contruction: Huib Nelissen

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

2 T_Visionarium; 2006, Scientia, UNSW, Sydney, Australia

Co-authors: Dennis Del Favero, Neil Brown, Matthew McGinity, Peter Weibel; Application software: Matthew McGinity; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: iCinema UNSW

3 Waterwalk; 1969, Sloterplas, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Co-authors: Theo Botschuijver, Sean Wellesley-Miller (Eventstructure Research Group);

Photo: Pieter Boersma

4 conFiguring the CAVE; 1997, NTT Intercommunication Centre, Tokyo, Japan;

Co-authors: Ágnes Hegedûs, Bernd Lintermann, Les Stuck (sound); Application software: Bernd Lintermann;

Photo: ICC Tokyo

5 Cloud (of daytime sky at night); 1970, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Projection mapped air-structure;

Co-authors: Theo Botschuijver, Sean Wellesley-Miller (Evenstructure Research Group) ;

Photo: Pieter Boersma

6 The Infinite Line; 2014, Chronus Art Centre, Shanghai, China;

Co-authors: Sarah Kenderdine, Edwin Nadason Thumboo; Application software: Leith Chan;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

7 The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway; 1975, Genesis World Tour; Projections, laser and inflatables performance

Co-author: Theo Botschuiver;

Photo: Evenstructure Research Group

8 unmakeablelove; 2008, eArts/eLandscapes, Shanghai, China, curated by Richard Castelli;

Co-author: Sarah Kenderdine; Mixed reality installation; Application software: Scot Ashton, Yossi Landesman, Conor O’Kane; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

9 The Virtual Museum; 1991, Das Belebte Bild, Art Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany, curated by Peter Weibel

Mixed reality installation; Application software: Gideon May; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

10 The Golden Calf; 1994, Ars Electronica, Linz, Austria

Augmented reality installation; Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

Application software: Gideon May

11 Once upon a time … we lived happily ever after; 1979, Gallery Bedaux, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Javaphile performance;

Photo: Javaphile Productions

Co-authors: Carlyle Reedy, Robert Hahn, John Munsey

12 Viewpoint; 1975, 9th Biennale de Paris, Musee d‘Art Moderne, Paris, France; Augmented reality installation;

Co-author: Theo Botschuijver; Photo: Eventstructure Research Group

13 Place – Hampi; 2006, Lille 3000, Lille, France, produced and curated by Richard Castelli;

Co-authors: Sarah Kenderdine, Paul Doornbusch (sound), John Gollings (photography), Dr. L. Subramaniam (music)

Application software: Adolf Mathias; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: Sarah Kenderdine, Jeffrey Shaw

14 Inventer la Terre; 1986, Cité des Sciences et de l´Industrie, La Villette, Paris, France; Augmented reality installation;

Co-author: Walter Maioli (sound);

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

15 Disillusionary Hommage to Clovis Trouille; 1966, Kasteelhoeve Beek En Donk, Netherlands; Expanded cinema installation;

Co-author: Tjebbe van Tijen;

Photo: Pieter Boersma

16 Corpocinema; 1967, Sigma Projects, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands; Expanded cinema performance;

Co-authors: Theo Botschuijver, Sean Wellesley-Miller, Tjebbe van Tijen

17 Smokescreen; 1969, Swansea Art Festival, University of Swansea, UK; Pyrotechnic performance;

Co-author: Theo Botschuiver; Photo: Eventstructure Research Group

18 Neon Waves; 1979, Koopvardersplantsoen, Amsterdam,

Netherlands; Interactive neon installation; Co-author:

Theo Botschuijver; Photo: Eventstructure Research Group

19 Virtual Sculpture; 1981, Melkweg, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Augmented reality installation;

Co-author: Theo Botschuijver; Application software: Larry Abel

Photo: Pieter Boersma

20 The Narrative Landscape; 1985, Aorta, Amsterdam, Netherlands;

Co-author: Dirk Groeneveld; Application software: Larry Abel;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

Anne-Marie Duguet

Jeffrey Shaw is a pioneer in the field of new media in numerous respects. The breadth of his influence is due not only to the experimental and radically anticipatory character of what he has produced, it is also the outcome of the context of the research work he has carried out since the early 1990s at several institutions. Equally important were the positions he held at ZKM—Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe and the UNSW iCinema (Sydney) and now holds at the CityU School of Creative Media in Hong Kong. He was thus able to conceive ambitious projects that did not have to conform to either the exigencies of a market or the criteria of legitimation of contemporary art, and were also not subject to economic constraints. His initiatives nurtured an attitude towards creativity and research that enabled him to encounter technology in a way that was free of prejudice and yet still permitted him to maintain a critical eye with respect to the utilization of this technology and its limitations. It is also to this formidable dynamism that one must pay tribute today.

The singularity of Jeffrey Shaw’s oeuvre already manifested itself in his first animated film and continues to do so today in his virtual environments—namely, the constant dialectic between the explicit appropriation of languages, techniques and models of representation derived from many different cultural traditions and the exploration of those new territories that technologies have opened up to him.

His first works—produced in the context of the intellectual, cultural and political ferment of the 1960s and 70s—manifest the principle paradigm shifts of contemporary art: refocusing attention towards the dispositif of representation and the prevailing conditions within which this representation is experienced; the involvement of the spectator in accordance with multiple perceptual, mental and behavioral modalities; the insistence on the process and the context of the work; the consideration given to history and memory; the interest in the heterogeneity of language; the collaboration among artists working in different disciplines; and, finally, the experimentation with alternative settings for art.

What emerged in particular over the course of these years is an artistic personality that gradually garnered recognition as an inventor of systems as well as a producer of specific technical and conceptual constellations that would later be referred to as dispositifs.

There is neither representation nor experience outside of a dispositif. In fact, it is the very condition of their possibility. Artistic installations, above all those of experimental cinema and video, have had the task of analyzing what constitutes the foundations of the dominant mode of representation since the Renaissance. It is not cinema or painting or the photo that is submitted to a meticulous re-examination but rather it is the entire ensemble of mythic and non-mythic dispositifs that is brought into consideration, from Plato’s cave to Brunelleschi’s tavoletta, from the camera obscura to Dürer’s perspectival gateway, from panoramas to contemporary surveillance systems. The entire history of representations is rehearsed every time in these theaters of seeing, whose heuristic function thus becomes quite clear.

This critical, analytical and reflexive dimension of the installation has been essential to Jeffrey Shaw’s oeuvre. In recombining various elements of the cinematic dispositif so as to allow unique configurations to develop out of them, as well as by coupling that dispositif of representation with other ones, the artist has repeatedly exposed the limits of the standard regulations of traditional cinema. Multiple screens, environmental projections, interactive scenes—the image is exceeded in every one of its dimensions, even at the level of its fullest and most complete nature.

The question of time has heavily impinged on artistic theory and practice since the 1960s. It has emerged not only as a recurrent theme but also as a constituent parameter of the very nature of an artwork. Performances, environments, events, installations have an exploratory duration, they are eminently contingent, closely tied to the specificity of a site or a context, and often dependent on the direct intervention of the audience. They necessarily incorporate chance and accident.

With these early works, Shaw began to conceive of an artwork as an “event structure” (a notion developed by John Latham),I a field of complex interactions composed of simultaneous events, each having its own duration (a performance act, the running time of a film, various physical phenomena).

Shaw then appropriated highly diverse techniques and elements, preferably fluid, evanescent, malleable, and inconsistent: water, fire, air, neon, polyethylene, pneumatic devices, pyrotechnics, films, photos, lasers etc. What counted was their ability “to physically embody the immaterial,” which still remains an issue and above all an interrogation at the heart of Shaw’s research.

Exceeding Architecture / Expanding Cinema

By adopting the principle of inflatable structures, Shaw exceeded the limits of architecture and proposed a soft architecture that is transformable, mobile, ephemeral and receptive to intermediate states. This concept was later developed further in Utopia Triumphans (2002). From a vocabulary of architectonic forms that pervade one another and protrude into a virtual space, a structure is permanently auto-generated in accordance with certain algorithms.

The critical and highly provocative approach of the Eventstructure Research Group (with whom Shaw produced his first pieces in 1967) entailed not only conceiving architecture as spatially fluid but also making it practicable. Pyramids, pavilions and domes became playful spaces able to produce unusual sensations for all visitors.

Right from the start, Shaw’s artistic practice addressed a broad audience, not merely that of art galleries. The desire to avoid making art a separate activity, to connect it to everyday life, prompted him to seek out new exhibition contexts such as a street, a facade or a canal. Neon Wave Sculpture (1979) was a kinetic light sculpture placed high on the side wall of a building. A luminous wave traveled through the neon tubes, describing a programmed pattern that was determined according to the speed of the wind. The artwork was thus rendered “sensitive” to natural phenomena and was open to chance factors (a key parameter in Cage-influenced experimentation of the day) including public intervention.

One important aspect of such pieces is the often collective nature of their production. The early 1960s saw increasing collaboration between artists from different fields. The Experiments in Art and Technology group (E.A.T.) for instance, was designed to spur encounters between artists, technicians and scientists. Such cooperation stemmed not only from the very nature of pieces that entailed complex technical and computational systems requiring specific skills, but also from a conception of artistic practice as ongoing work, activity, process and experimentation that escape the control of a single artist. Art was no longer a question of a sole creator’s subjectivity. This attitude has been a driving force behind Jeffrey Shaw’s output; he has always collaborated with several programmers as well as with writers, composers, artists and art historians.II

As much as architecture, Shaw appropriated cinema to re-work its constituent principles. With his first installation, Emergence of Continuous Forms (1966), he inaugurates a series of “expanded cinema environments”, expanded in space by projecting his film onto a series of semi-transparent screens set up over the length of the gallery, as well as by the intervention of visitors who could modify one screen by inflating it.

The question of the screen—be it three-dimensional and borderless or a viewing window—has been central to Shaw’s thinking; he subjected it to a multitude of trials, steadily challenging its specific qualities: paper screens are torn, smoke screens dissipate etc. The image printed on the film strip is no longer the main center of interest, rather it is the uncertain status of the projected image, the image-in-formation. Film projection itself thus becomes a performance. Shaw declared, “all my works are a discourse, in one way or another, with the cinematic image, and with the possibility to violate the boundary of the cinematic frame—to allow the image to physically burst out towards the viewer, or allow the viewer to virtually enter the image.”III Two “performance events” produced in the Netherlands in 1967, Corpocinema and MovieMovie, sum up his exploration of this notion of expansion. The “corpocinematic concept” also meant giving body to film, endowing it with volume, the third dimension that it lacked.

lt was not the arrival of digital simulation and the resulting possibilities of specifically interactive modes that prompted Jeffrey Shaw to interrogate the relationship between spectator and artwork. His environments, events and installations, although the ones not employing computer technology, necessarily implied and defined procedures of involvement that went beyond simple levels of contemplation, identification or interpretation. What clearly emerged then was the idea of the audience’s responsibility, that its presence as well as a deliberate intervention was an integral part of the overall process.

A retrospective look raises one point of particular interest, namely the way in which Shaw immediately generated experimental fields and experiential “occasions” that involved the human body in playful, poetic actions, and that were, in a way, precursors to the perceptual situation now offered to travelers in virtual worlds. Impressions of immersion, floating and suspension were all effects engendered at the time by provocative concepts like Shaw’s “soft responsive architecture.” They belong to an initial group of experiments on the notion of environment as organic space.

Anticipating Augmented Reality

Well before the use of computers, Viewpoint (1975) provides a good example of Shaw’s systematic investigation into the nature of virtual images and of the potential of installations that he began to explore for exposing representational processes. This work powerfully inaugurated the total dependence between the image and its spectator, as in a mirror situation. An image was no longer given, could not pre-exist its actualization—here, its perception by a spectator. The point of view became the very site and condition of visibility. In several other pieces, such as The Golden Calf, The Virtual Museum or the series of Place, the construction of optical illusion was dependent on the perfect coincidence of the spot from where the photograph or video was shot, the source of the image projected (or displayed on a screen) and the position of the observer.

The radicalization of the process of virtualizing images inevitably led to the complete abolition of the screen. Thus right from the late 1970s Shaw began developing a “see-through virtual reality system” based on stereoscopic principles. His optical device (a forerunner of the head-mounted display HMD and BOOM) coupled a semi-transparent mirror with a computer screen onto which two wire-frame images of a cube were displayed. The spectator could observe the basic rotation of the cube projected onto the room, integrated with the other elements of the space. In this Virtual Projection Installation (1978) the original function of the “screen” had completely evolved toward a “viewing system” but it was henceforth in the hands of the spectator. With Points of View (1983), the image became an environment to be activated and transformed. Once the spectator enters the scene, representation lost its autonomy and become a theater of operations.

Virtual Totality and the Panoramic Impulse

For the interactive sculpture Inventer La Terre (1986), Shaw developed another viewing device comprising a small video monitor and a periscope installed in a column with an opening in the middle through which the spectator looked at the exhibition space. By rotating the column, the viewer selected various sites to explore within a virtual panorama; floating travelogue images of the selected site then appeared superimposed onto the exhibition space. Tales, signs and symbols taken from ancient times and cultures on various continents, expressed the multiplicity of representations of the world, constituting what Shaw calls a kind of “museum within the museum.” This work, meanwhile, crystallized a major notion within his own oeuvre, namely “virtual totality,” based on the twin principles of the viewing window and the panorama.

Since Diadrama (1974) devised for a theatrical stage, Shaw developed his work on environmental immersive projection through various dispositifs, based on a sphere or a cylinder, exploiting the model of the panorama. Place—A User’s Manual (1995) combines and reinterprets two key elements of the 19th-century panoramas: the circular screen and the central observation platform. The image is projected onto the screen from a small rotating platform where the visitor stands, providing a privileged point of observation. Since the image covers only one third of the screen, the observer can generate a total view of the panorama solely through time and a continuous sweep. The spectator’s memory and capacity for anticipation are required to complete the environment. The dialectic between global and fragmented view, already present in several of Shaw’s pieces, becomes all the more striking in Place—A User’s Manual insofar as total vision is precisely what the panorama promises. But while the viewer gains the control of exploration and the feeling of power it confers, he has to deal with a constant negotiation between manipulation and contemplation.

Cultural Heritage

The television screen of Revolution (1990), which fully assumed the metaphor of a “window on the world”, displayed the vast visual memory of revolutions since 1789. Visitors were invited to turn the wheel of history and access a series of images constituting humanity’s collective memory.

In more recent works Place—Hampi (2006) or Pure Land—Inside the Magao Grottoes at Dunhuang (2012), both in collaboration with Sarah Kenderline, Shaw pursues research on World Heritage sites by exploiting these two similar environmental systems: the panorama as re-worked in the Place series, and the AVIE,IV a stereoscopic interactive visualization and audio environment. With a cylinder twice as high as Place, it is the most immersive system conceived by Shaw, to be explored with polarizing glasses, which eliminate the distance to the scene and isolate the viewer from the actual environment. The realism of the experience is reinforced by the 1:1 scale of high-resolution photography and the surrounding sound system.

Photography fixes the memory of an architectural grouping. However, the myth escapes any capture and its “documentation” can only be the actualization of an imaginary representation. By activating the high-resolution panoramas of the archeological site of Vijayanagara in Hampi, one comes across beings that are not photographic but animated representations. Digital characters inhabit these spaces as “living” gods and mythical figures from the Ramayana, bringing to life an ancestral collective memory, evoking contemporary beliefs about the creation of the site.

Pure Land is another “theater of memory” in which the visitor can explore one painting of the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas with a device simulating a torch light, or a magnifying glass to look into details. Here 3D animations are also called on, giving poetic and historical information such as ritual dances or musical instruments of the time.

With this undeniable way of preserving an exceptional heritage two main issues are at stake. First, a methodological bet: getting back closer to the project of the historical panoramas with advanced technology, it provides a persuasive surrogate kinesthetic experience of a site, based on immersion and narrative to stimulate the imagination and desire for discovery. Secondly, the multi-layered interpretation of the site history and of its various cultural elements, this “augmented memory” resulting partly from reconstitutions, question the “document” as a given trace speaking by itself. As Michel Foucault stress in The Archaeology of Knowledge, the primary task of history now in relation to the document is: “to work on it from within and to develop it [...] trying to define within the documentary material itself unities, totalities, series, relations.”V

Discontinuity and Simultaneity in Narrative

Structures

Different forms of narrative are at work in most of Shaw’s installations: autonomous micro-narratives in Viewpoints which the spectator can access in no particular or predetermined order, or narrative lines to follow/read in the calculated streets and 3D architectural texts of Legible City. Parallel narrations respond to the multiplicity of points of view, often in the mode of a fragment, without links but with passages and with possible leaps from the one to the other. Meanings are largely produced by the spectator from a virtually discontinuous linearity. Beyond the text itself, it is the very conception of potential pathways—the manner in which the text/ image “happens”—that enables a reader to develop his/her own branching rhizomes.

The “theater of signs” of the first Shaw works has given place to scenes performed by actors as in Eavesdrop (2004) or The Infinite Line (2014) with the poet Edwin Tumboo. Nevertheless a very singular narrative engagement between users and virtual characters is at stake in UNMAKEABLELOVE (2008), in collaboration with Sarah Kenderline. Computer- generated human bodies VI perform, with a paradoxically autonomous obsessive behavior in a prison- like space. Inspired by The Lost Ones by Samuel Beckett, there is no text but a complex dispositif based on a surveillance system of the other and of the self simultaneously. The visitors, outside a hexagonal construction, the Re-Actor, referring to the model of the Kaiser panorama, peer into this virtual cage with probing torch lights replacing the windows of the Panopticon and surveillance cameras.

What makes Shaw’s approach so innovative does not so much lie in his exploration of some of the most advanced techniques available, as it does in his invention of interfaces. As the executor of transactions between the virtual and real, the interface is necessarily at the heart of his research. Inseparable from the whole dispositif, it is part of a whole web of metaphors. Shaw creates architectures/ interfaces that respond both together to the conceptual requirements of a particular project, and to the perceptual conditions of these new works that the virtual environments are, repeatedly, inventing other ways of seeing and experiencing a work.

The text includes excerpts from Anne-Marie Duguet’s essay published in: Duguet, A-M., Klotz, H., Weibel, P. (1997). Jeffrey Shaw—A User’s Manual: From Expanded Cinema to Virtual Reality, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

I John Latham, artist, taught film at Saint Martins School of Art, London, where Shaw studied in 1966.

II Collaborators include: software developers—Larry Abel, Gideon May, Adolf Mathias, Bernd Lintermann, Matt McGinity, Leith Chan; writers—Dirk Groeneveld, David Pledger; composers—Harry de Wit, Les Stuck, Paul Doornbusch, Torsten Belschner; artists—John Latham, Tjebbe van Tijen, Theo Botschuijver, Agnes Hegedues, Dennis Del Favero, Bernd Lintermann, Saburo Teshigawara, Peter Weibel, The Wooster Group, Jean Michel Bruyere, Sarah Kenderdine.

III Jeffrey Shaw in discussion with Ueno Toshiya: “We are Materialists, We Employ Science and Technology to Concretize the Virtual,” in Media Passage, ed. lnterCommunication Center, Tokyo, 1993, p. 53.

IV AVIE (Advanced Visualisation and Interaction Environment) collaboration Jeffrey Shaw, Dennis Del Favero, Matthew McGinity, Ardrian Hardjono, Volker Kuchelmeister. UNSW iCinema Centre, Sydney. AVIE is “a cylindrical silver projection screen 4 meters high and 10 meters in diameter. It has a set of 5 high-resolution digital video projectors that together project an active 3D 1000 x 8000 pixel stereoscopic picture over the entire 360-degree surface of the screen.” (cf www.epidemic.net)

V Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge, Pantheon Books, New York, 1972, p.6-7 Trans. A.M. Sheridan Smith

VI “The obsessive behaviours of these inhabitants have been motion captured, computationally animated and then rendered in real-time using a game engine and ALife and algorithms.” (Shaw and Kenderline’s description)

Anne-Marie Duguet (FR) is Professor Emeritus at University of Paris1 Pantheon-Sorbonne. She is the author of books such as Vidéo, la mémoire au poing (1981), Jean-Christophe Averty (1991), Déjouer l’image. Créations électroniques et numériques (2002). Art critic and curator: Jean-Christophe Averty (Espace Electra, Paris 1991); Thierry Kuntzel. (Jeu de Paume, Paris, 1993); Smile Machines (Akademie der Kunst, Berlin, 2006); co-curator of Artifices Biennale, Saint-Denis, (1994, 1996). Director of the multimedia series anarchive (Muntadas, Snow, Kuntzel, Otth, Nakaya, Fujihata).

Photos

1 The Legible City, 1989-91, Artec, Nagoya, Japan

Co-author: Dirk Groeneveld; Application software: Gideon May; Contruction: Huib Nelissen

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

2 T_Visionarium; 2006, Scientia, UNSW, Sydney, Australia

Co-authors: Dennis Del Favero, Neil Brown, Matthew McGinity, Peter Weibel; Application software: Matthew McGinity; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: iCinema UNSW

3 Waterwalk; 1969, Sloterplas, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Co-authors: Theo Botschuijver, Sean Wellesley-Miller (Eventstructure Research Group);

Photo: Pieter Boersma

4 conFiguring the CAVE; 1997, NTT Intercommunication Centre, Tokyo, Japan;

Co-authors: Ágnes Hegedûs, Bernd Lintermann, Les Stuck (sound); Application software: Bernd Lintermann;

Photo: ICC Tokyo

5 Cloud (of daytime sky at night); 1970, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Projection mapped air-structure;

Co-authors: Theo Botschuijver, Sean Wellesley-Miller (Evenstructure Research Group) ;

Photo: Pieter Boersma

6 The Infinite Line; 2014, Chronus Art Centre, Shanghai, China;

Co-authors: Sarah Kenderdine, Edwin Nadason Thumboo; Application software: Leith Chan;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

7 The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway; 1975, Genesis World Tour; Projections, laser and inflatables performance

Co-author: Theo Botschuiver;

Photo: Evenstructure Research Group

8 unmakeablelove; 2008, eArts/eLandscapes, Shanghai, China, curated by Richard Castelli;

Co-author: Sarah Kenderdine; Mixed reality installation; Application software: Scot Ashton, Yossi Landesman, Conor O’Kane; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

9 The Virtual Museum; 1991, Das Belebte Bild, Art Frankfurt, Frankfurt, Germany, curated by Peter Weibel

Mixed reality installation; Application software: Gideon May; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

10 The Golden Calf; 1994, Ars Electronica, Linz, Austria

Augmented reality installation; Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

Application software: Gideon May

11 Once upon a time … we lived happily ever after; 1979, Gallery Bedaux, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Javaphile performance;

Photo: Javaphile Productions

Co-authors: Carlyle Reedy, Robert Hahn, John Munsey

12 Viewpoint; 1975, 9th Biennale de Paris, Musee d‘Art Moderne, Paris, France; Augmented reality installation;

Co-author: Theo Botschuijver; Photo: Eventstructure Research Group

13 Place – Hampi; 2006, Lille 3000, Lille, France, produced and curated by Richard Castelli;

Co-authors: Sarah Kenderdine, Paul Doornbusch (sound), John Gollings (photography), Dr. L. Subramaniam (music)

Application software: Adolf Mathias; Construction: Huib Nelissen;

Photo: Sarah Kenderdine, Jeffrey Shaw

14 Inventer la Terre; 1986, Cité des Sciences et de l´Industrie, La Villette, Paris, France; Augmented reality installation;

Co-author: Walter Maioli (sound);

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

15 Disillusionary Hommage to Clovis Trouille; 1966, Kasteelhoeve Beek En Donk, Netherlands; Expanded cinema installation;

Co-author: Tjebbe van Tijen;

Photo: Pieter Boersma

16 Corpocinema; 1967, Sigma Projects, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands; Expanded cinema performance;

Co-authors: Theo Botschuijver, Sean Wellesley-Miller, Tjebbe van Tijen

17 Smokescreen; 1969, Swansea Art Festival, University of Swansea, UK; Pyrotechnic performance;

Co-author: Theo Botschuiver; Photo: Eventstructure Research Group

18 Neon Waves; 1979, Koopvardersplantsoen, Amsterdam,

Netherlands; Interactive neon installation; Co-author:

Theo Botschuijver; Photo: Eventstructure Research Group

19 Virtual Sculpture; 1981, Melkweg, Amsterdam, Netherlands; Augmented reality installation;

Co-author: Theo Botschuijver; Application software: Larry Abel

Photo: Pieter Boersma

20 The Narrative Landscape; 1985, Aorta, Amsterdam, Netherlands;

Co-author: Dirk Groeneveld; Application software: Larry Abel;

Photo: Jeffrey Shaw

Jeffrey Shaw was born in 1944 in Melbourne, Australia. From 1962 to 1966, Shaw studied architecture and art history at the University of Melbourne, and sculpture at the Brera Academy in Milan and at the St. Martins School of Art in London. Shaw was co-founder of the Eventstructure Research Group in Amsterdam (1969-1979), and founding director of the ZKM Institute for Visual Media Karlsruhe (1991-2002). At the ZKM he conceived and ran a seminal artistic research program that included the ArtIntAct series of digital publications, the MultiMediale series of international media art exhibitions, and over one hundred artist-in-residence projects. In 1995, Shaw was appointed Professor of Media Art at the State University of Design, Media and Arts (HfG), Karlsruhe, Germany. In 2003 Jeffrey Shaw was awarded the prestigious Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship and returned to Australia to co-found and direct the UNSW iCinema Centre for Interactive Cinema Research in Sydney from 2003-2009. In 2009 Shaw joined City University of Hong Kong as Chair Professor of Media Art and Dean of the School of Creative Media (SCM). In 2014 Shaw received an honorary doctorate in creative media from the Multimedia University, Malaysia, and was appointed visiting professor at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing, and visiting professor at the Institute for Global Health Innovation, Imperial College, London. In recognition of his major international impact on the field, Shaw has won several awards for his new media projects and publications, including the Ars Electronica Honorable Mention for Interactive Art, Linz, Austria, 1989; the Immagine Elettronica Prize, Ferrara, Italy, 1990; the Oribe Award, Gifu, Japan, 2005 and the Lifetime Achievement Award, Society of Art and Technology, Montreal, Canada, 2014. (Source: Jeffrey Shaw)