ARS ELECTRONICA ARCHIVE - PRIX

Der Prix Ars Electronica Showcase ist eine Sammlung, innerhalb derer die Einreichungen der KünstlerInnen zum Prix seit 1987 durchsucht und gesichtet werden können. Zu den Gewinnerprojekten liegen umfangreiche Informationen und audiovisuelle Medien vor. ALLE weiteren Einreichungen sind mit den Basisdaten in Listenform recherchierbar.

Jasia Reichardt

Jasia Reichardt

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_Art_at_Home_inPeoplesHome1996_2075088.jpg | 4007 * 4992px | 7.8 MB | Art at Home, an exhibition in people's homes,

Copenhagen, 1996

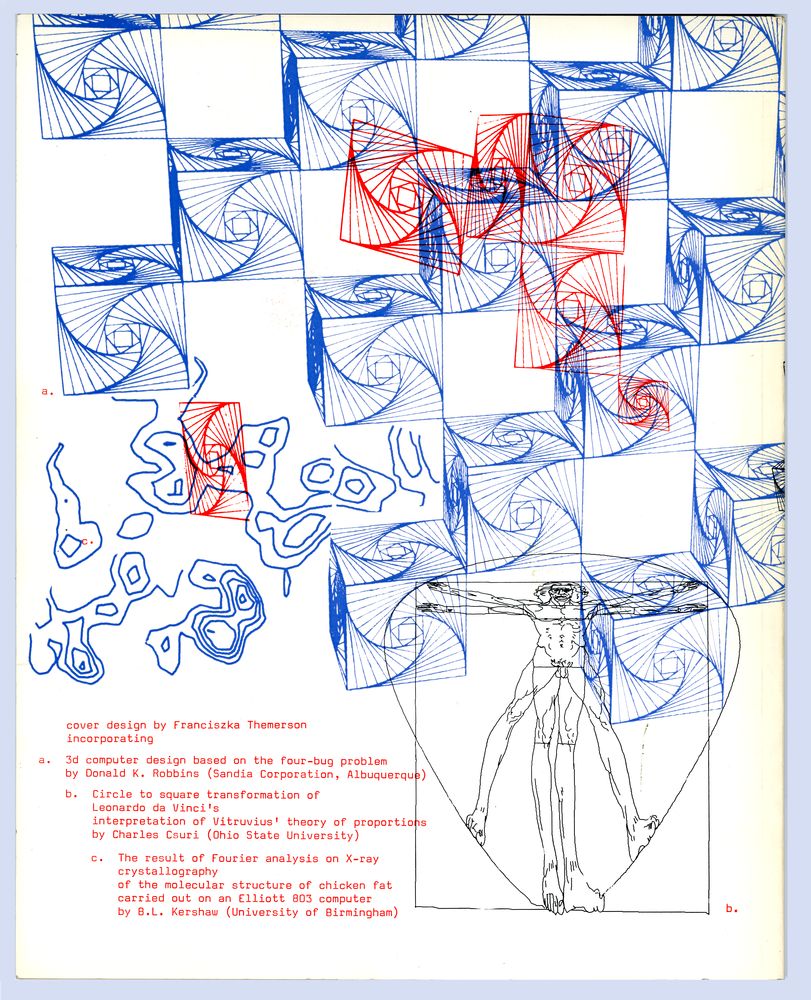

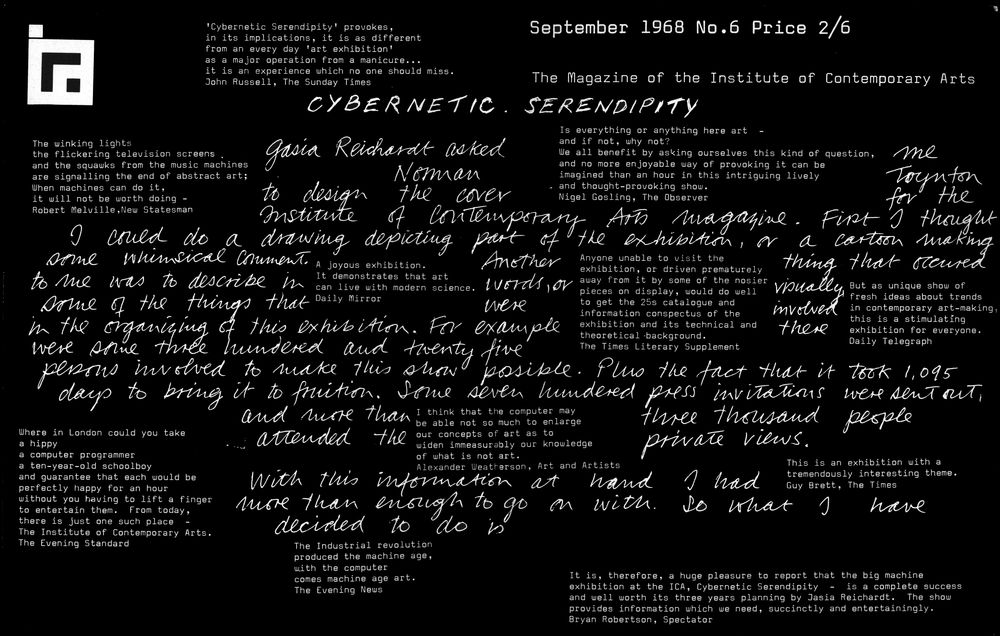

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_BackCover_StudioInternationalPublication_2075090.tif | 6093 * 7514px | 36.5 MB | Back Cover of the Studio International publication accompanying Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, ICA,

London, 1968; Cover design by Franciszka Themerson, designer of the exhibition

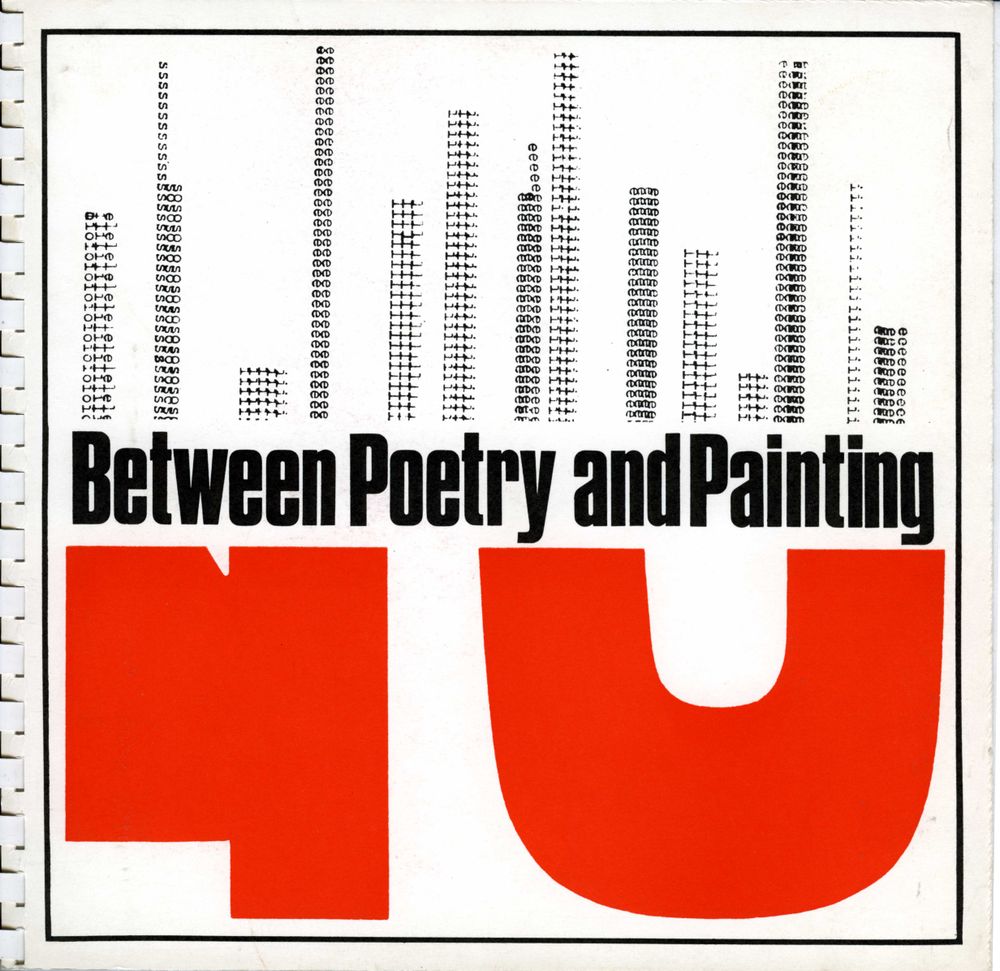

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_BetweenPoetryandPainting_2075100.jpg | 4926 * 4784px | 1.8 MB | First London exhibition of concrete poetry, ICA London 1965

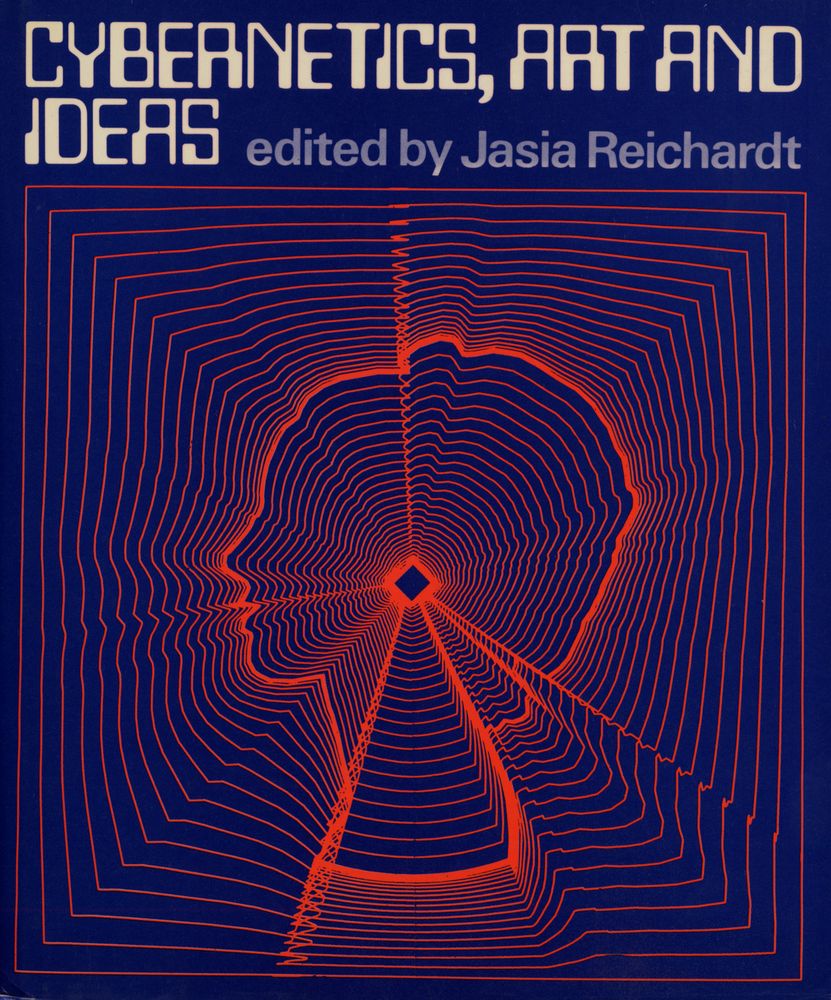

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_CyberneticsArtandIdeas_2075096.jpg | 4972 * 5983px | 4.0 MB | Cybernetics Art and Ideas, Studio Vista 1971

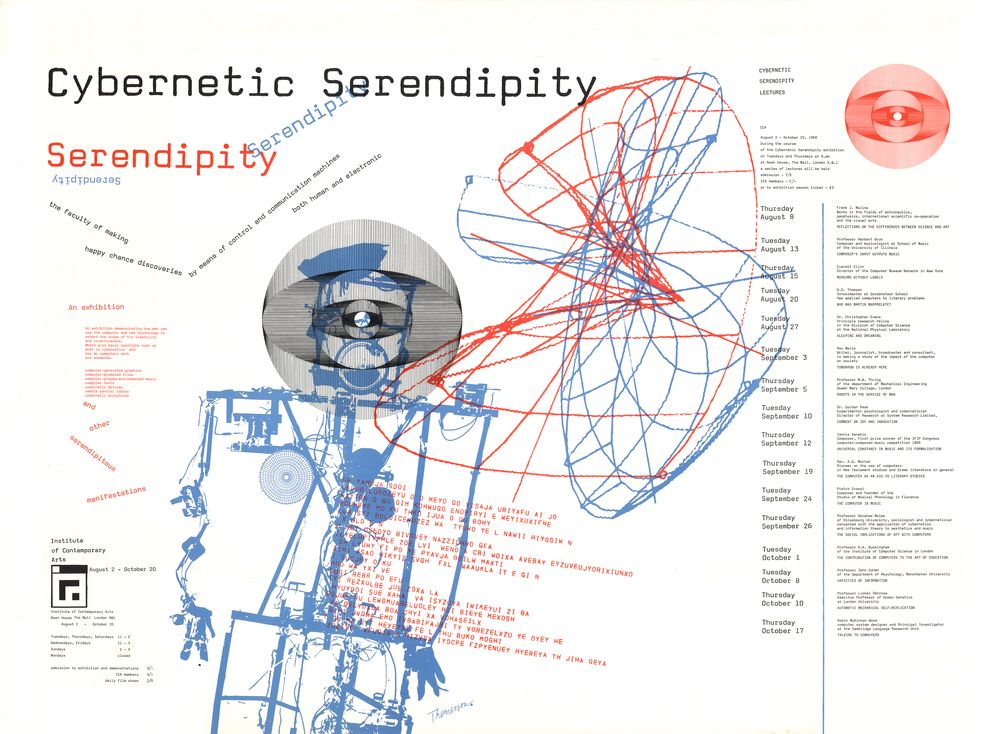

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_CyberneticSerendipityExhibitionPoster_2075092.tif | 12020 * 8832px | 73.2 MB | Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition poster designed by Franciszka Themerson

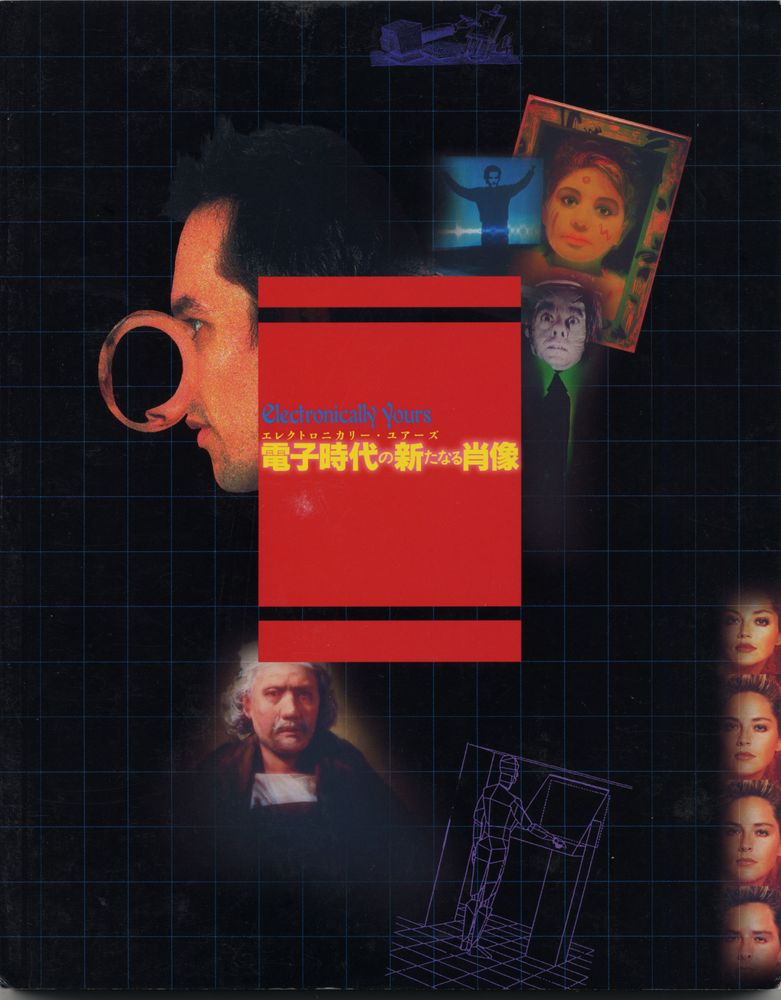

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_ElectronicallyYours_exhibition_2075098.jpg | 5291 * 6775px | 3.3 MB | Electronically Yours exhibition, Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 1998

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_exhibition_HerbertReads75birthday_1065_2075086.jpg | 4761 * 5248px | 4.5 MB | An exhibition to celebrate Herbert Read's 75th

birthday, New London Gallery and Marlborough

Fine Art, London, 1965

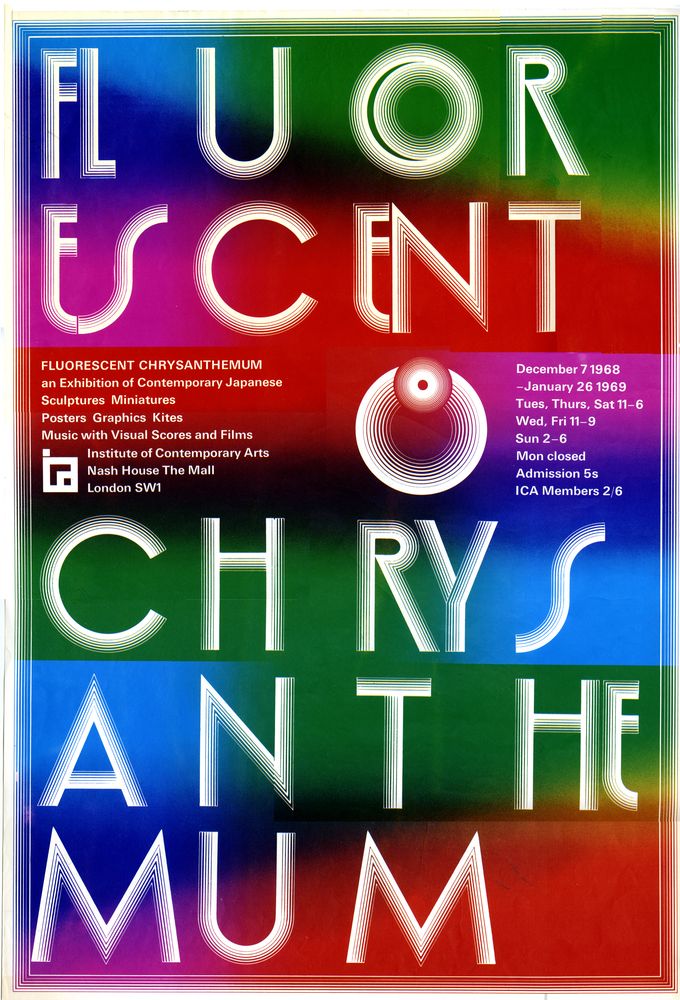

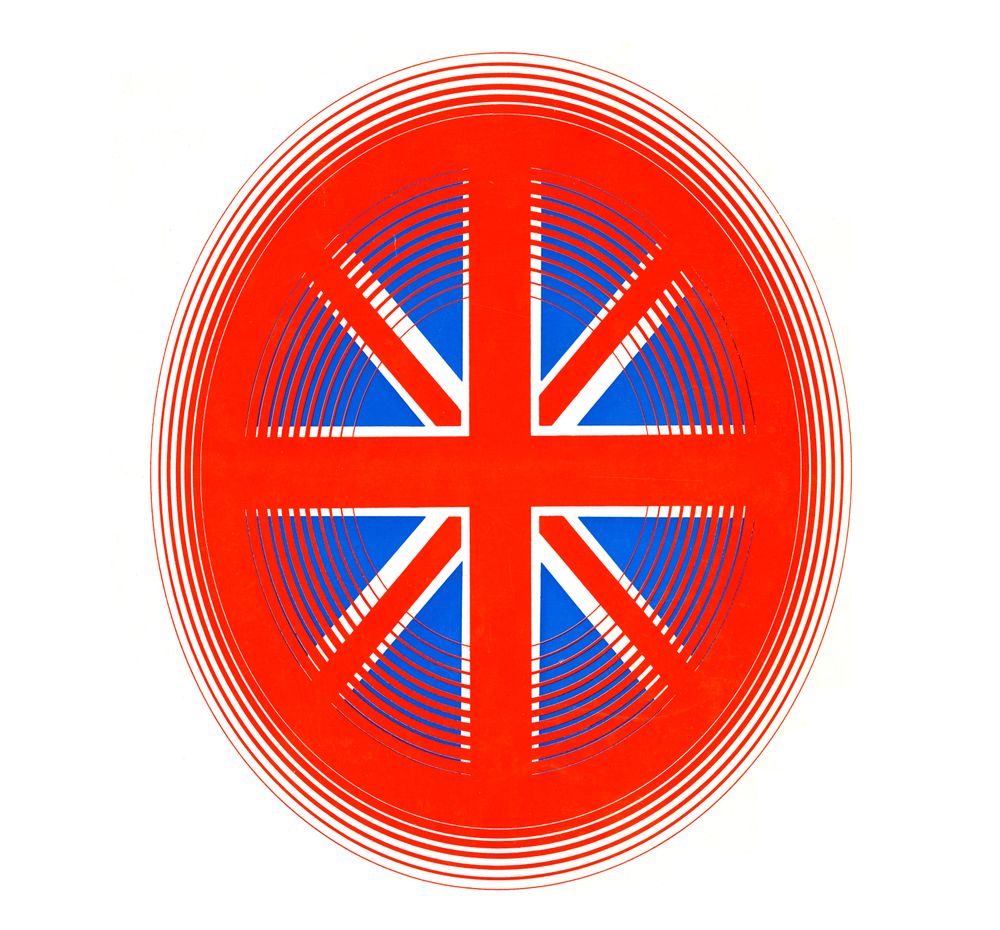

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_FluorescentChrysanthemum_2075102.tif | 4497 * 6614px | 70.4 MB | Fluorescent Chrysanthemum, exhibition poster, ICA, London, 1968-69

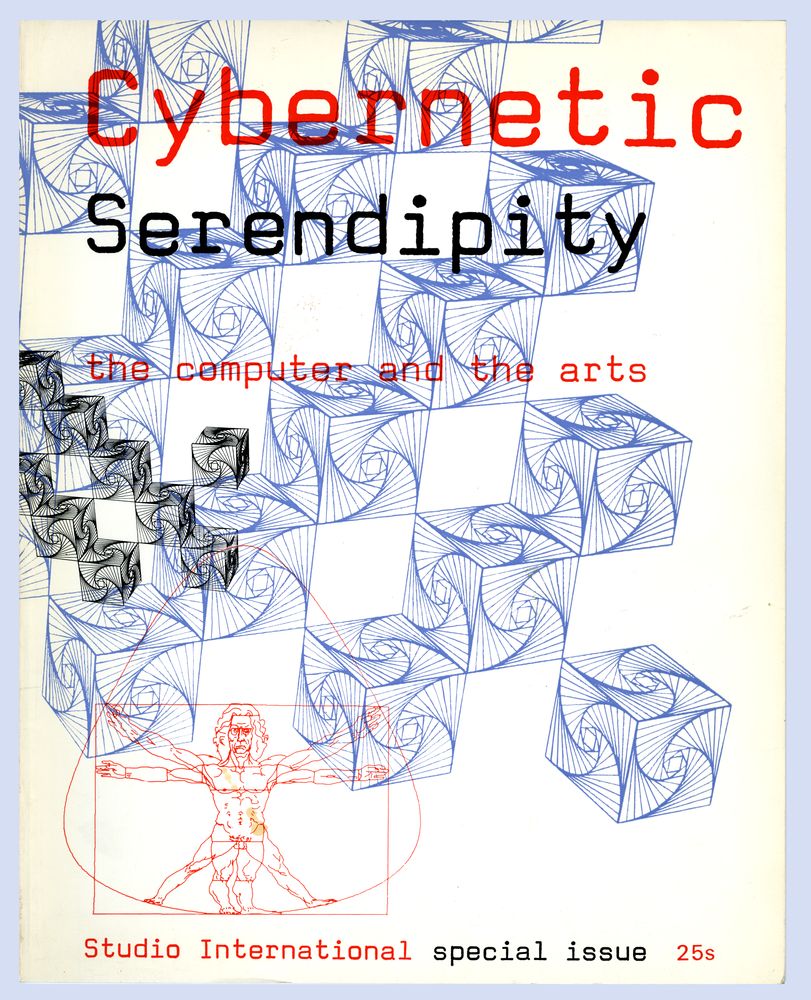

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_FrontCover_StudioInternationalPublication_2075104.tif | 6093 * 7514px | 49.9 MB | Front cover of the Studio International publication accompanying Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition, ICA, London, 1968; Cover design by Franciszka Themerson, designer of the exhibition

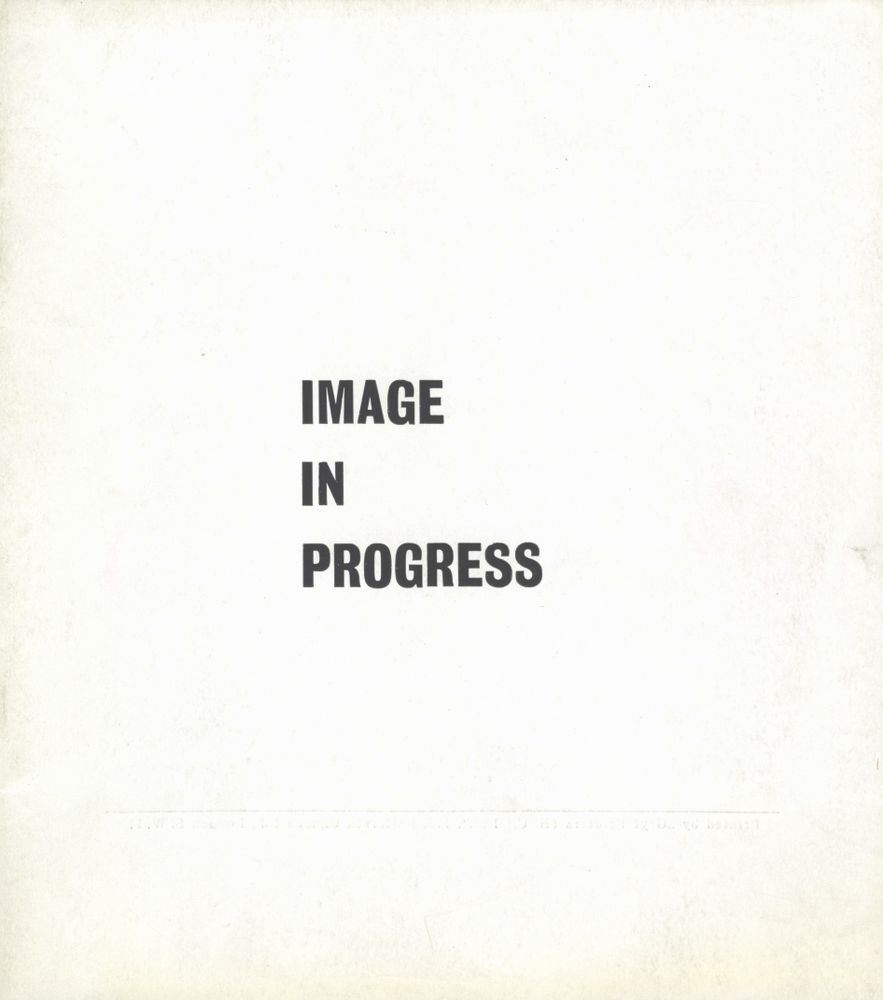

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_ImageInProgressExhibiton_2075108.jpg | 3781 * 4283px | 1.5 MB | Image in Progress exhibition, Grabowski Gallery, London, 1962

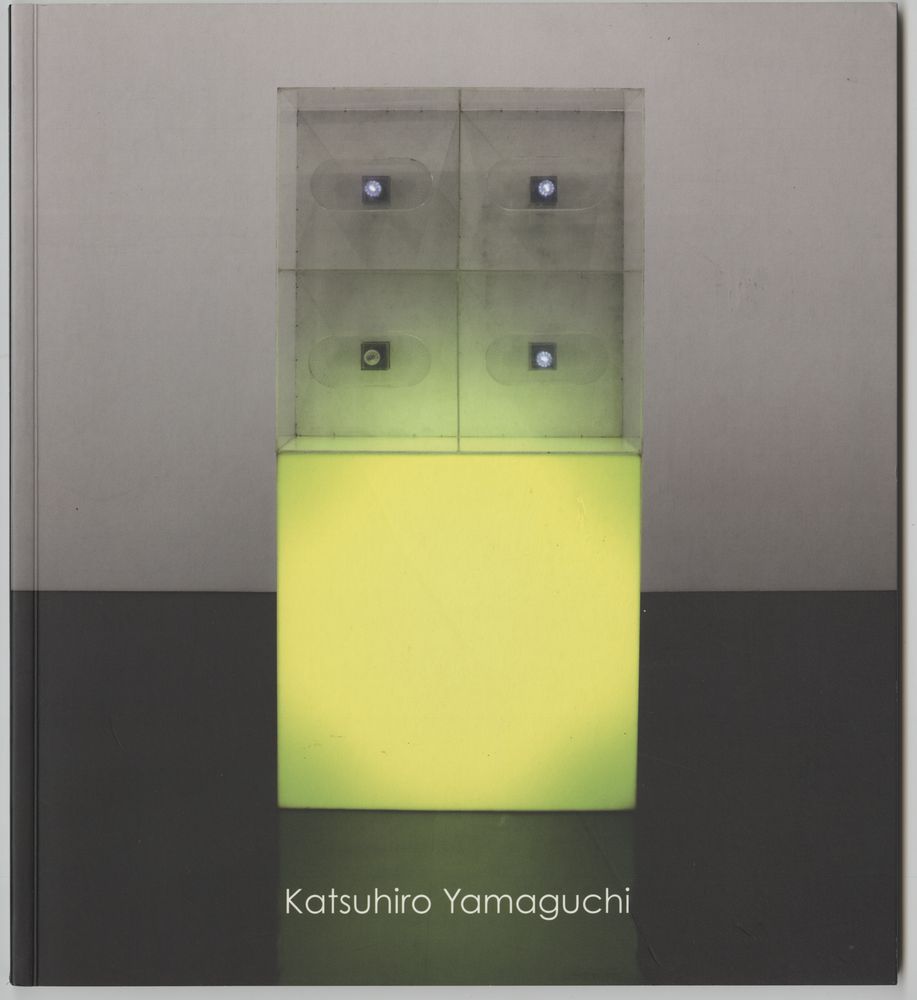

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_KasuhiroYamaguchi_2075114.tif | 4725 * 5154px | 44.0 MB | Katsuhiro Yamaguchi, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, 2013

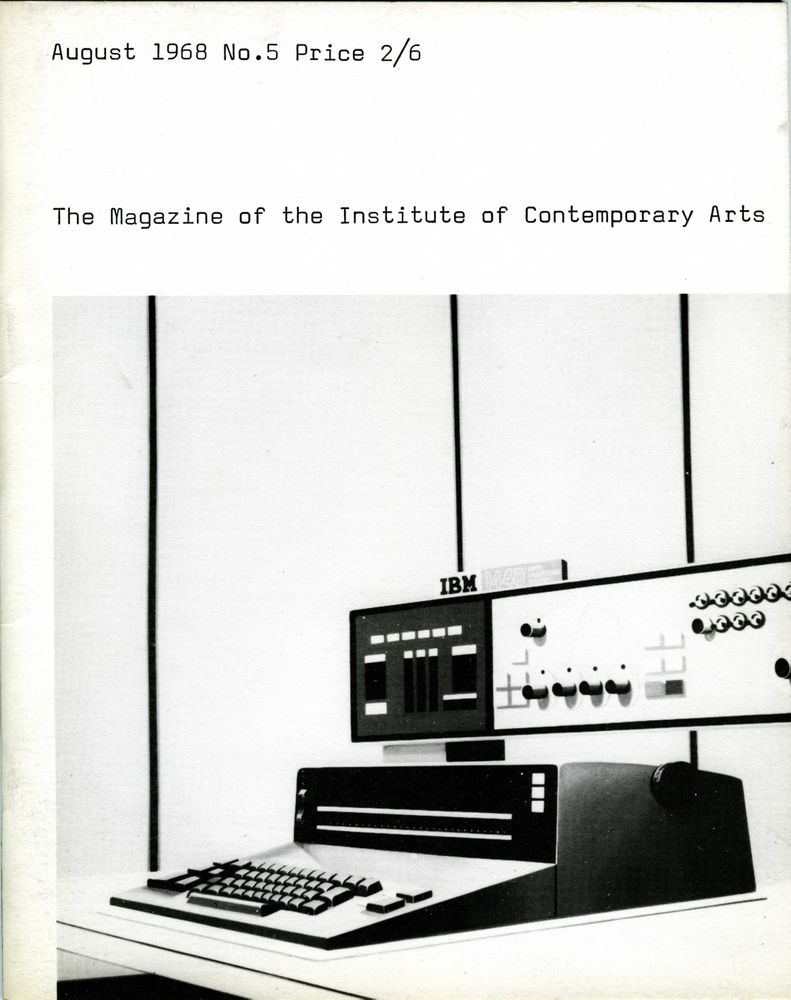

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_MagazineOfTheInstituteOfContemporaryArts_2075136.jpg | 4480 * 5661px | 6.7 MB | First issue of the ICA magazine devoted to Cybernetic Serendipity. Image on the cover is Lowell Nesbitt’s painting of IBM 1440 Data Processing System, 1965

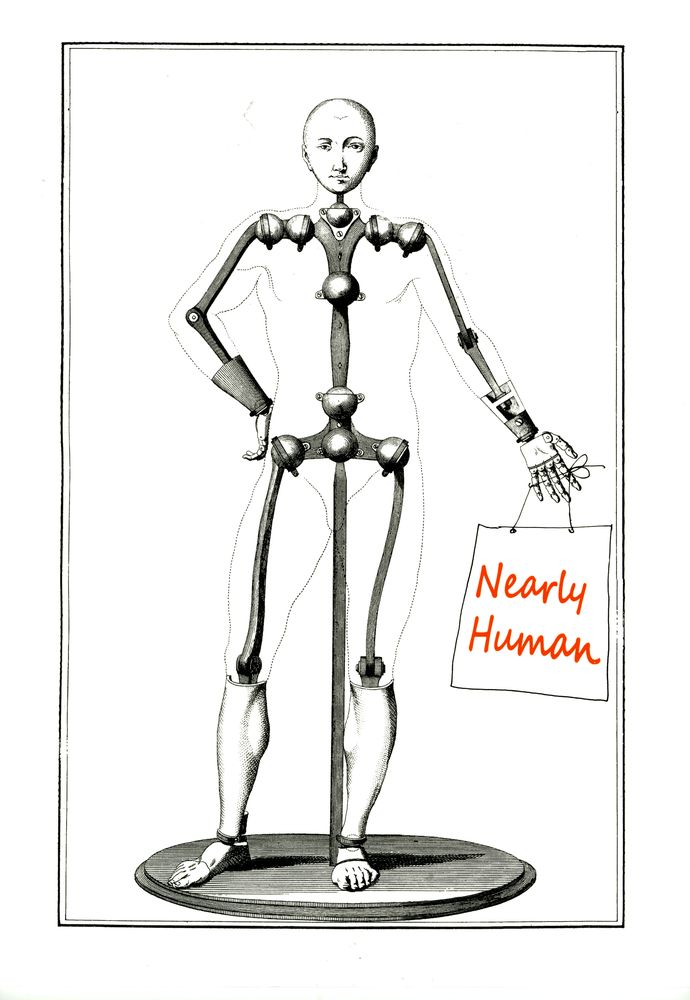

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_NearlyHuman_exhibition_2075118.tif | 4853 * 7032px | 12.6 MB | Nearly Humann exhibition Łaźnia Gdansk 2015

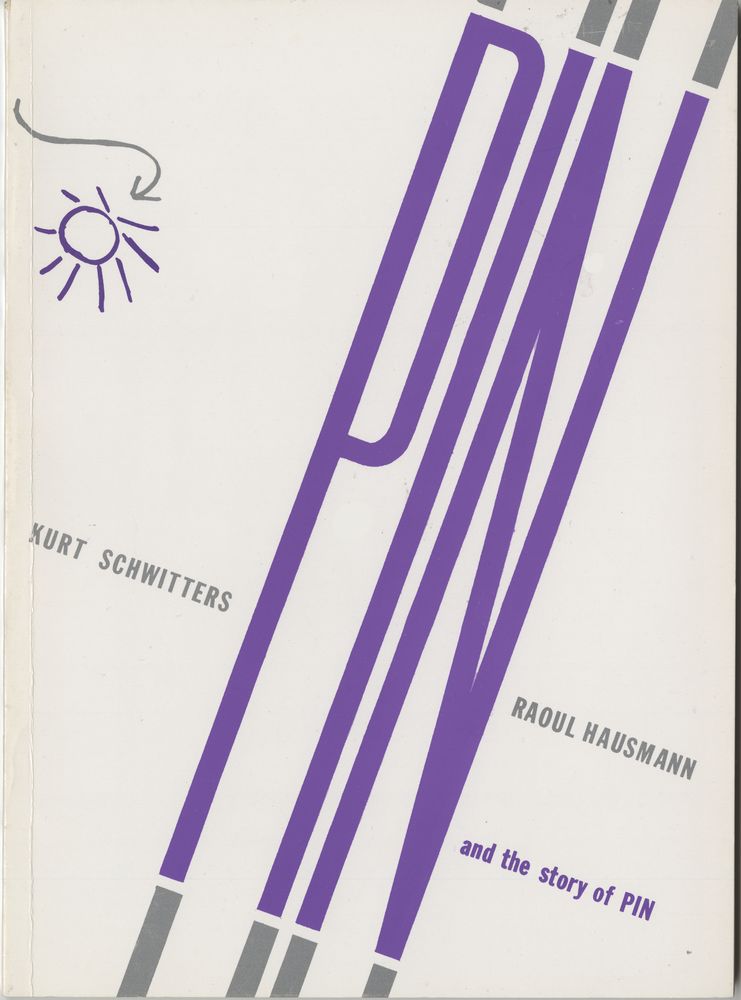

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_PINandthestoryofPin_2075116.tif | 4165 * 5618px | 30.6 MB | Kurt Schwitters & Raoul Hausmann, PIN and the story of PIN, Gaberbocchus Press, London, 1962

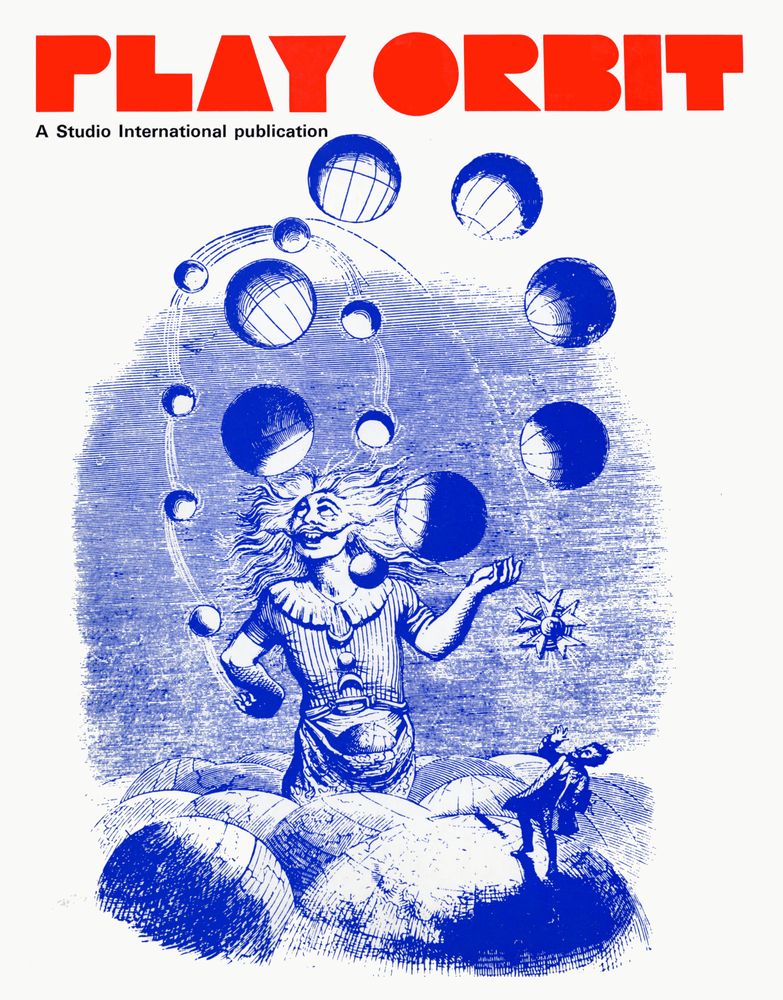

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_PlayOrbit_Grandville_Cover_2075106.jpg | 5682 * 7256px | 5.2 MB | Grandville cover for the catalogue of Play Orbit exhibition, ICA, 1969

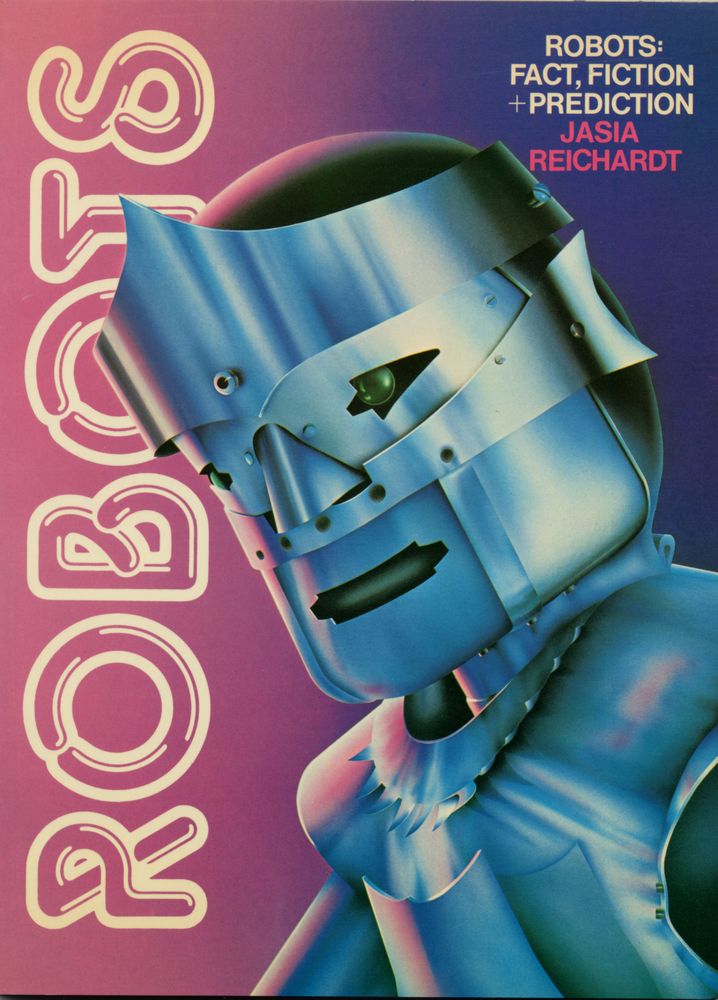

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_Robots_2075120.jpg | 4750 * 6610px | 3.1 MB | Robots: Fact, Fiction and Prediction, Thames & Hudson, 1978

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_secondIssueofICAmagazine_2075122.tif | 6616 * 4209px | 3.6 MB | Second issue of the ICA magazine

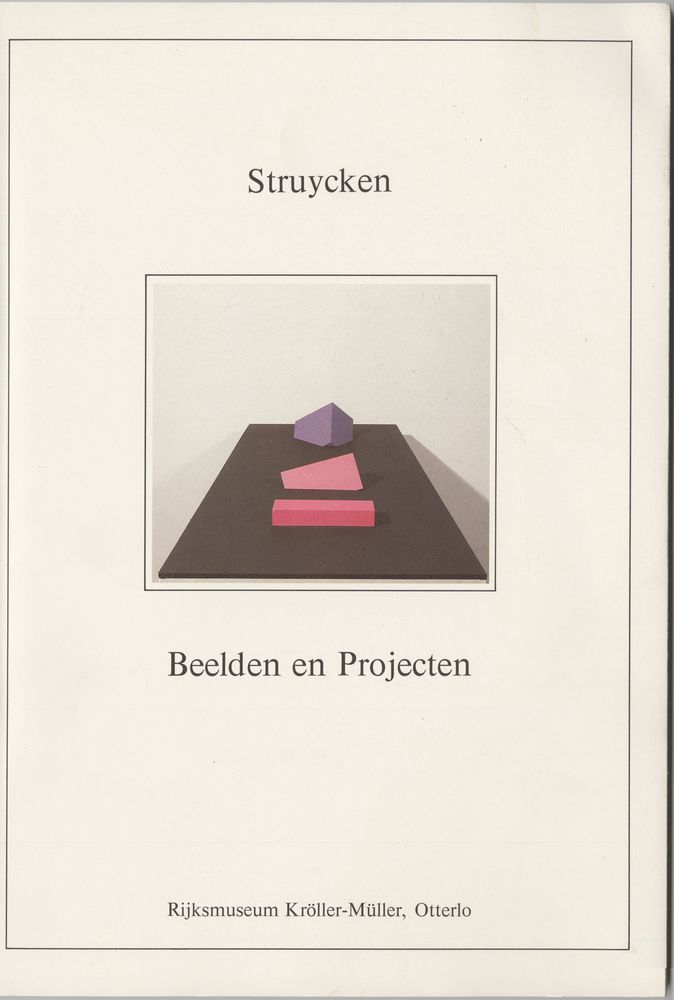

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_Struycken_2075124.tif | 4722 * 7005px | 57.4 MB | Struycken, Beelden en Projecten, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, 1977

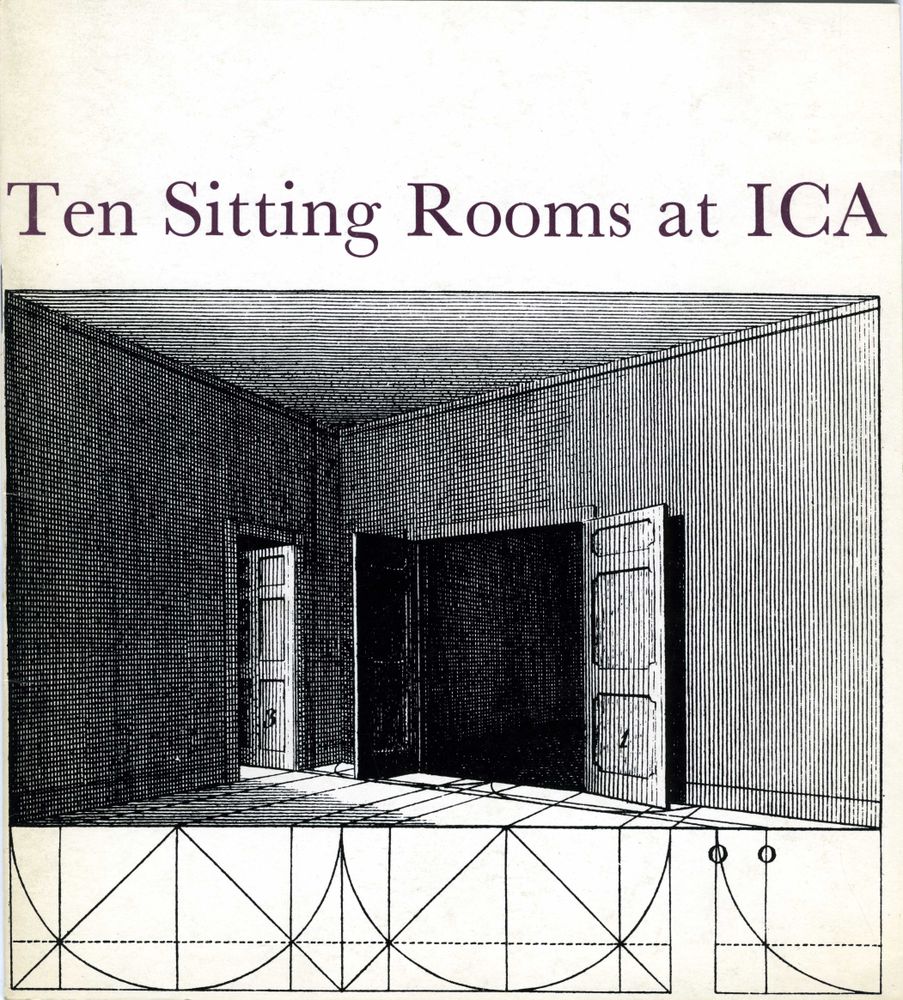

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_Ten_Sitting_Rooms_2075126.jpg | 4204 * 4657px | 4.8 MB | Ten Sitting Rooms, ICA, London, 1970

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_the4thExhibition_2075128.jpg | 6184 * 5752px | 6.6 MB | The 4th Exhibition for the First Prize of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Nagaoka, 1967. Catalogue cover designed by Kohei Sugiura

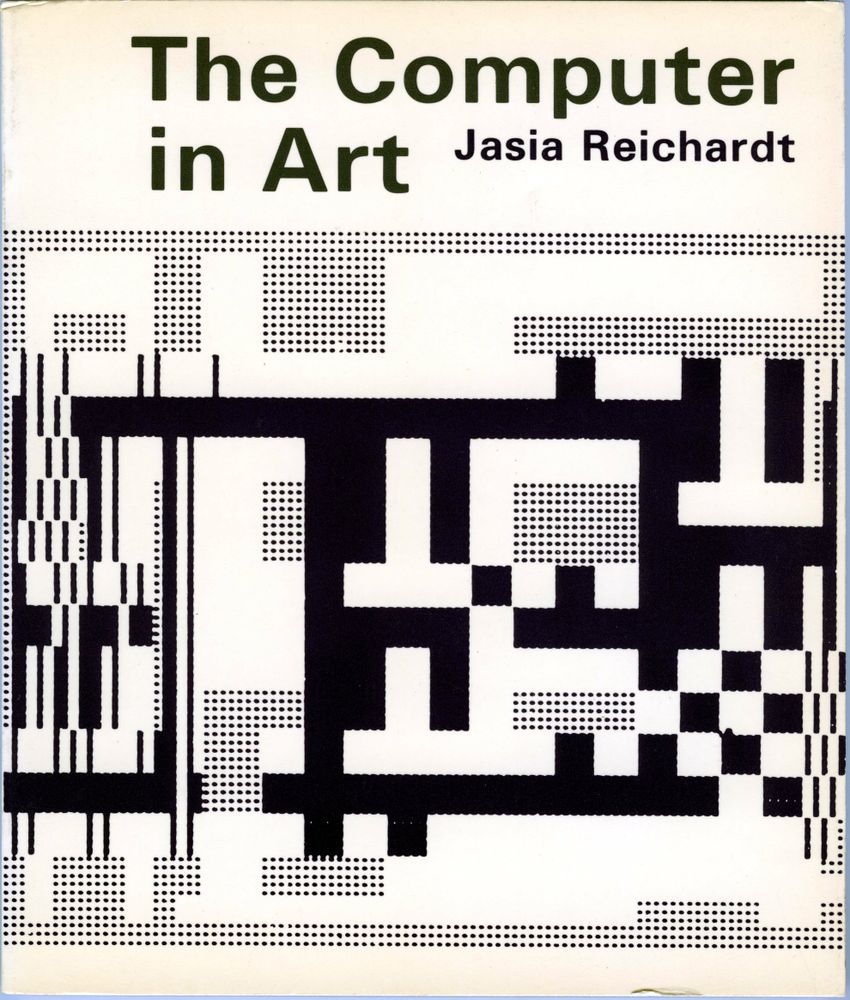

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_theComputerInArt_2075130.jpg | 3958 * 4657px | 3.4 MB | The Computer in Art, Studio Vista, 1971

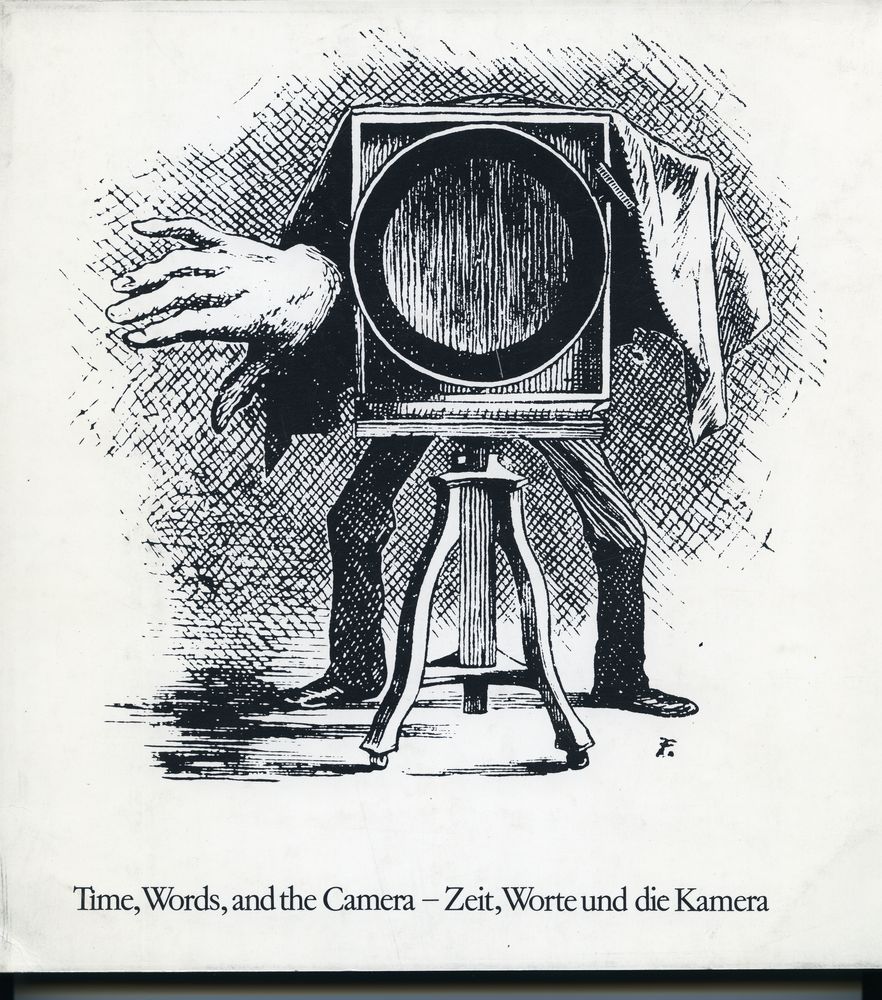

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_Time_words_andTheCamera_2075132.tif | 4988 * 5655px | 80.7 MB | Back covers of the catalogue Time, words, and the camera: photoworks by British artists.

Künstlerhaus, Graz, 1976

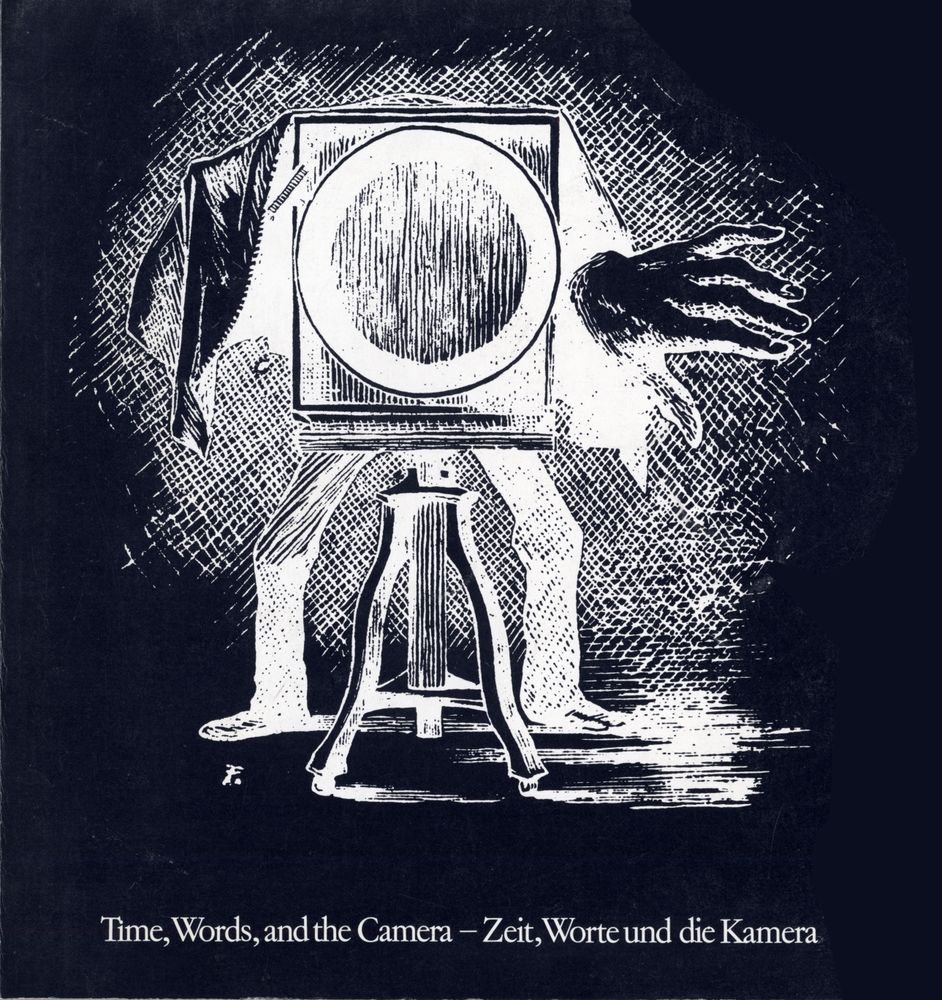

Original: VP_160001_221153_AEC_PRX_2016_Time_words_andTheCamera_2_2075134.jpg | 5153 * 5472px | 3.2 MB | Front cover of the catalogue Time, words, and the camera: photoworks by British artists.

Künstlerhaus, Graz, 1976

Jasia Reichardt—A Life on a Plate

When Jasia Reichardt received an honorary doctorate from Middlesex University in 2015, she was asked which aspects of her work she was most proud of. She mentioned two things that none of us expected. The first was her appointment as Madame President of Section X (General) of the British Association of the Advancement of Science in 1982. She invented, organised, chaired and gave a presidential address at the conference on “The Power of Fashion in Art and Science” (Speakers included: Margaret Boden, Colin Brewer, Bernard Dixon, Brian Goodwin, Tim Gordon, Hans Keller, Helmut Kirchner, Edward Lucie-Smith, John Maddox, Jonathan Miller, Bill Pirie, Tim Souster, Stefan Themerson). Yes, the conference was about fashion, that powerful force which obscures judgement, sways opinions and distorts objectivity in all fields of human endeavour.

The second was the 8-volume catalogue of the Themerson Archive, on which she worked for 20 years and which will be published by the Polish National Library early next year (in English, of course).

So, why didn’t she mention all her work with art and technology for which she is so well known: the exhibitions Cybernetic Serendipity, Electronically Yours, Nearly Human, the publications and lectures on computer art, robots, automata, and media?

Perhaps because these subjects were/are the mainstay of her professional life, to be taken for granted. They occupy and invade her thinking. When did it all start, this interest in art and technology and art and science? After all, she studied neither. It probably goes back to 1958, when at the Gaberbocchus Common Room, the first regular London meeting place for artists and scientists, she heard a lecture about cybernetics.

Did she study anything? Yes, the theatre. She wanted to be a director of intellectual entertainments. Perhaps that’s what she became but her theatre became a gallery, the slideshow, a lecture hall, or the printed page.

Her interest in machines has a long history, because at the age of four her mother told her about a machine that could wash and iron clothes without any human intervention. Yes, she decided, one day, she too would have such a machine. The year was 1937, and, of course, at the time no such machines were on the horizon.

When, twenty years later, Jasia became an art critic in London and worked as assistant editor of Art News and Review, she was interested in the avant-garde and in ideas that connected art to other areas of creative activity on the borderlines of the art world. At the time these included concrete poetry, design, kinetic and light art.

Before I tell you something about her work, her projects realised and unrealised, I’d like to describe her life, her home. She lives with her partner, Nick Wadley, art historian and artist, who gets involved in all her projects. Their house is white and full of paper, paintings and plants. Ceilings are high and it is usually cold. There is a collection of robots, toy robots plus an AIBO, which is a recent addition. It is one of the earliest models. Her book on robots, published in 1978, is still considered to be one of the best books covering the history of the subject, and there is a trunk of articles, correspondence and photographs dealing with the history of robots. Not surprisingly, this collection continues to grow. It is, of course, one of several collections of ephemera that provide basic research material. One of the collections deals with art and technology, science, computers, AI, the future; another deals with artists, living and dead. Still paper: catalogues, newspaper cuttings, invitations, press releases, of which the time of production is always revealed in texture, size, typeface and colour. You don’t always need a printed date to know when something was published. Her own archive of writings and correspondence, some of it filed, is in white boxes. Her published work in a four-drawer filing cabinet.

She doesn’t like to talk about herself because everything she thinks about seriously is in her writings. If she talks, it is about the amusing things that happened in her life, anecdotes, unrepeatable events. Here are two examples:

It is 1970, and Jasia Reichardt is a member of the Experimental Projects Committee of the Arts Council. Mark Boyle is in the chair, Nick Serota, who works for the Arts Council, takes notes. The committee, there are some seven members, go through the usual motions of committee meetings with the reading of minutes and going through the agenda of examining the proposals submitted by artists to decide who should receive financial support. On that particular occasion one of the projects is an extremely well designed, beautifully detailed geometric construction, a wall relief, which appeals to all the members of the committee, and this is the project that the committee decides to support. When the projects are completed, the artists photograph them, and send the photographs to the committee in time for the next meeting. When the photograph arrives, there was a stunned silence: in his house the winning artist installed wall-to-wall central heating. Jasia breaks out in uncontrollable laughter.

It is 1975, and Jasia Reichardt is the director of London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery. It is a requirement of the Trustees and in her contract that once a year, there should be an exhibition of local artists. At the time, the East End of London is not the mecca of artists that it became 40 years later, and Jasia doesn’t like amateur art. Even so, rules have to be followed, and an announcement inviting contributions to the exhibition The Flower Show of Tower Hamlets (an answer to the famous annual Chelsea Flower Show) is sent out in English, Urdu and Hindi to various local centres, schools, hospitals, etc. giving information about the sending-in days. Several art students of St Martin’s School of Art are employed to receive the works and to display them. On the first sending-in day, nothing arrives. On the second, nothing. On the third, two small works. The exhibition is to open two days later. What to do? The students are asked to create a flower show. In two days, the students transform the gallery and the staircase into a garden with trees, bushes, giant flowers and a swing, against green walls. The exhibition looks wonderful and the trustees trot in for the opening. “It’s lovely”, they say to Jasia. “We told you that there is a lot of talent in the East End”.

Her work at Art News and Review finished in 1960 and then followed the first of three periods of freelancing. She was writing regularly for Architectural Design, ’L’Art d’Aujourd’hui, and other art publications.

In 1962, she organised the first exhibition of English Pop Art at Grabowski Gallery in South Kensington. It was called Image in Progress and included seven young artists from the Royal College of Art: Derek Boshier, David Hockney, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, Max Shepherd, Norman Toynton and Brian Wright. The Inner Image followed two years later, also at Grabowski Gallery. That exhibition of the Leicester Group included works which combined painting with sculpture. Her next exhibition in 1965, after she became assistant director at the ICA, was the first London exhibition of concrete poetry: Between Poetry and Painting. She then teaches at Bath Academy of Art, edits the monthly ICA Bulleting, and is thinking of new exhibitions.

Mike Sarne, in his article, “la clique belsize parkienne”, in art and artists, May 1966, wrote about her: “… probably the most influential art critic on the scene is in that fortunate position for a variety of reasons, but possibly can count on two cardinal virtues: first, she knows everyone, and, second, she never knocks anyone.”

Her work? Since 1962, when she organised her first exhibition at the Grabowski Gallery, she has curated some thirty exhibitions, including all the shows at the Whitechapel Art Gallery when she was its director, February 1974 – April 1976. Her most recent exhibition that is about human imagination, called Nearly Human, is still travelling, and will continue to do so. Apart from the historical section about robots, automata and marionettes, new works of art can be added as others leave. New things are imagined and ideas change as the artists define and make what to them is “nearly human”, and the show progresses from one venue to another.

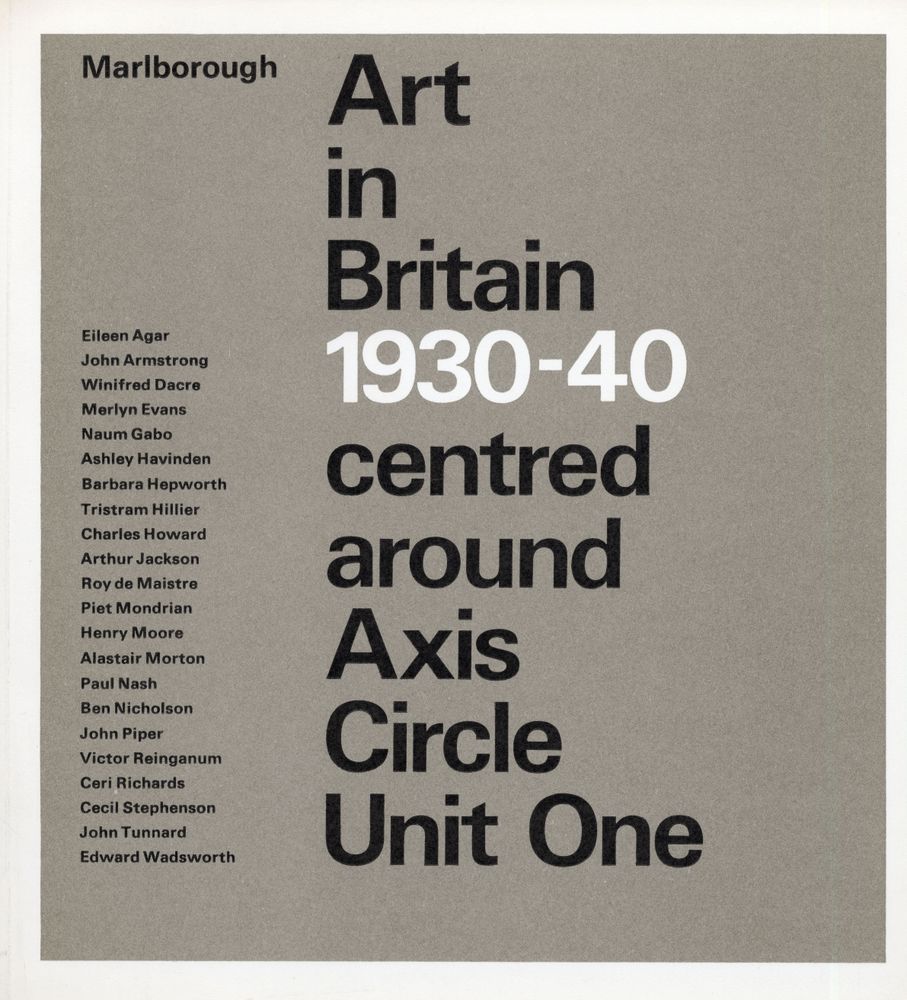

Some of the catalogue covers of Jasia’s exhibitions are illustrated on these pages, as well as some of the covers of the books she has written.

Several of the projects she has been especially fond of and worked on for many years, are unrealised. For instance, there is the Fantasia Mathematica, a project for visualising mathematics, 1972, that was to be an exhibition, a book and a television programme. There is also, the Automatic Music Theatre, an exhibition with circular arena in which music machines created by artists play music by themselves, performing only when a spotlight is directed onto them. The lighting system, however, like life, is unpredictable, with the result that some of the machines have more chances of performing then others. History of the Future, her book about afterlife, with a screenplay about an adventurous protagonist escorted around various sites of heaven and hell, is still sitting quietly in the cupboard.

Many years ago Jasia Reichardt wrote articles under several pseudonyms, but this time she has written the above in the third person and without pretending to be anyone else.

When Jasia Reichardt received an honorary doctorate from Middlesex University in 2015, she was asked which aspects of her work she was most proud of. She mentioned two things that none of us expected. The first was her appointment as Madame President of Section X (General) of the British Association of the Advancement of Science in 1982. She invented, organised, chaired and gave a presidential address at the conference on “The Power of Fashion in Art and Science” (Speakers included: Margaret Boden, Colin Brewer, Bernard Dixon, Brian Goodwin, Tim Gordon, Hans Keller, Helmut Kirchner, Edward Lucie-Smith, John Maddox, Jonathan Miller, Bill Pirie, Tim Souster, Stefan Themerson). Yes, the conference was about fashion, that powerful force which obscures judgement, sways opinions and distorts objectivity in all fields of human endeavour.

The second was the 8-volume catalogue of the Themerson Archive, on which she worked for 20 years and which will be published by the Polish National Library early next year (in English, of course).

So, why didn’t she mention all her work with art and technology for which she is so well known: the exhibitions Cybernetic Serendipity, Electronically Yours, Nearly Human, the publications and lectures on computer art, robots, automata, and media?

Perhaps because these subjects were/are the mainstay of her professional life, to be taken for granted. They occupy and invade her thinking. When did it all start, this interest in art and technology and art and science? After all, she studied neither. It probably goes back to 1958, when at the Gaberbocchus Common Room, the first regular London meeting place for artists and scientists, she heard a lecture about cybernetics.

Did she study anything? Yes, the theatre. She wanted to be a director of intellectual entertainments. Perhaps that’s what she became but her theatre became a gallery, the slideshow, a lecture hall, or the printed page.

Her interest in machines has a long history, because at the age of four her mother told her about a machine that could wash and iron clothes without any human intervention. Yes, she decided, one day, she too would have such a machine. The year was 1937, and, of course, at the time no such machines were on the horizon.

When, twenty years later, Jasia became an art critic in London and worked as assistant editor of Art News and Review, she was interested in the avant-garde and in ideas that connected art to other areas of creative activity on the borderlines of the art world. At the time these included concrete poetry, design, kinetic and light art.

Before I tell you something about her work, her projects realised and unrealised, I’d like to describe her life, her home. She lives with her partner, Nick Wadley, art historian and artist, who gets involved in all her projects. Their house is white and full of paper, paintings and plants. Ceilings are high and it is usually cold. There is a collection of robots, toy robots plus an AIBO, which is a recent addition. It is one of the earliest models. Her book on robots, published in 1978, is still considered to be one of the best books covering the history of the subject, and there is a trunk of articles, correspondence and photographs dealing with the history of robots. Not surprisingly, this collection continues to grow. It is, of course, one of several collections of ephemera that provide basic research material. One of the collections deals with art and technology, science, computers, AI, the future; another deals with artists, living and dead. Still paper: catalogues, newspaper cuttings, invitations, press releases, of which the time of production is always revealed in texture, size, typeface and colour. You don’t always need a printed date to know when something was published. Her own archive of writings and correspondence, some of it filed, is in white boxes. Her published work in a four-drawer filing cabinet.

She doesn’t like to talk about herself because everything she thinks about seriously is in her writings. If she talks, it is about the amusing things that happened in her life, anecdotes, unrepeatable events. Here are two examples:

It is 1970, and Jasia Reichardt is a member of the Experimental Projects Committee of the Arts Council. Mark Boyle is in the chair, Nick Serota, who works for the Arts Council, takes notes. The committee, there are some seven members, go through the usual motions of committee meetings with the reading of minutes and going through the agenda of examining the proposals submitted by artists to decide who should receive financial support. On that particular occasion one of the projects is an extremely well designed, beautifully detailed geometric construction, a wall relief, which appeals to all the members of the committee, and this is the project that the committee decides to support. When the projects are completed, the artists photograph them, and send the photographs to the committee in time for the next meeting. When the photograph arrives, there was a stunned silence: in his house the winning artist installed wall-to-wall central heating. Jasia breaks out in uncontrollable laughter.

It is 1975, and Jasia Reichardt is the director of London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery. It is a requirement of the Trustees and in her contract that once a year, there should be an exhibition of local artists. At the time, the East End of London is not the mecca of artists that it became 40 years later, and Jasia doesn’t like amateur art. Even so, rules have to be followed, and an announcement inviting contributions to the exhibition The Flower Show of Tower Hamlets (an answer to the famous annual Chelsea Flower Show) is sent out in English, Urdu and Hindi to various local centres, schools, hospitals, etc. giving information about the sending-in days. Several art students of St Martin’s School of Art are employed to receive the works and to display them. On the first sending-in day, nothing arrives. On the second, nothing. On the third, two small works. The exhibition is to open two days later. What to do? The students are asked to create a flower show. In two days, the students transform the gallery and the staircase into a garden with trees, bushes, giant flowers and a swing, against green walls. The exhibition looks wonderful and the trustees trot in for the opening. “It’s lovely”, they say to Jasia. “We told you that there is a lot of talent in the East End”.

Her work at Art News and Review finished in 1960 and then followed the first of three periods of freelancing. She was writing regularly for Architectural Design, ’L’Art d’Aujourd’hui, and other art publications.

In 1962, she organised the first exhibition of English Pop Art at Grabowski Gallery in South Kensington. It was called Image in Progress and included seven young artists from the Royal College of Art: Derek Boshier, David Hockney, Allen Jones, Peter Phillips, Max Shepherd, Norman Toynton and Brian Wright. The Inner Image followed two years later, also at Grabowski Gallery. That exhibition of the Leicester Group included works which combined painting with sculpture. Her next exhibition in 1965, after she became assistant director at the ICA, was the first London exhibition of concrete poetry: Between Poetry and Painting. She then teaches at Bath Academy of Art, edits the monthly ICA Bulleting, and is thinking of new exhibitions.

Mike Sarne, in his article, “la clique belsize parkienne”, in art and artists, May 1966, wrote about her: “… probably the most influential art critic on the scene is in that fortunate position for a variety of reasons, but possibly can count on two cardinal virtues: first, she knows everyone, and, second, she never knocks anyone.”

Her work? Since 1962, when she organised her first exhibition at the Grabowski Gallery, she has curated some thirty exhibitions, including all the shows at the Whitechapel Art Gallery when she was its director, February 1974 – April 1976. Her most recent exhibition that is about human imagination, called Nearly Human, is still travelling, and will continue to do so. Apart from the historical section about robots, automata and marionettes, new works of art can be added as others leave. New things are imagined and ideas change as the artists define and make what to them is “nearly human”, and the show progresses from one venue to another.

Some of the catalogue covers of Jasia’s exhibitions are illustrated on these pages, as well as some of the covers of the books she has written.

Several of the projects she has been especially fond of and worked on for many years, are unrealised. For instance, there is the Fantasia Mathematica, a project for visualising mathematics, 1972, that was to be an exhibition, a book and a television programme. There is also, the Automatic Music Theatre, an exhibition with circular arena in which music machines created by artists play music by themselves, performing only when a spotlight is directed onto them. The lighting system, however, like life, is unpredictable, with the result that some of the machines have more chances of performing then others. History of the Future, her book about afterlife, with a screenplay about an adventurous protagonist escorted around various sites of heaven and hell, is still sitting quietly in the cupboard.

Many years ago Jasia Reichardt wrote articles under several pseudonyms, but this time she has written the above in the third person and without pretending to be anyone else.

Jasia Reichardt is a writer on art and an exhibition organiser. Born in Poland, educated in England, she has lived in London most of her life. She was Assistant Director of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, 1963-71, and Director of the Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1974-76. She has taught at the Architectural Association and other colleges, has written for most of the international art magazines and contributed to many international exhibitions and conferences throughout the world. She is principally interested in the relationship between art and science, art and technology, art and the history of ideas, and this is why some of her best known exhibitions, such as Between Poetry and Painting (1965) and Cybernetic Serendipity (1968), were about the connections between one field and another. She has written several books, including The Computer in Art (1971), and Robots—Fact, Fiction and Prediction

(1978), and edited Cybernetics, Art and Ideas (1971). She also worked on visualisation of mathematics, a project called, Fantasia Mathematica. In 1982, she was President of a conference on The Power of Fashion in Art & Science for the British Association for the Advancement of Science, of whose committee she was a member 1982-92. She was one of the directors of ARTEC biennale in Japan 1989-1998. Also in 1998, she curated an exhibition of electronic portraiture, called Electronically Yours, at Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. She continues to pursue her interests in the relationship of art and technology and other borderlines of art. Since 1988 she has been looking after the Themerson Archive, the archive of a writer and an artist, whose avant-garde publishing company, Gaberbocchus Press, launched a Common Room for artists interested in science and scientists interested in the arts in 1957. Her latest exhibition, Nearly Human, is about machines and objects that are nearly like us—all products of our imagination.

(1978), and edited Cybernetics, Art and Ideas (1971). She also worked on visualisation of mathematics, a project called, Fantasia Mathematica. In 1982, she was President of a conference on The Power of Fashion in Art & Science for the British Association for the Advancement of Science, of whose committee she was a member 1982-92. She was one of the directors of ARTEC biennale in Japan 1989-1998. Also in 1998, she curated an exhibition of electronic portraiture, called Electronically Yours, at Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography. She continues to pursue her interests in the relationship of art and technology and other borderlines of art. Since 1988 she has been looking after the Themerson Archive, the archive of a writer and an artist, whose avant-garde publishing company, Gaberbocchus Press, launched a Common Room for artists interested in science and scientists interested in the arts in 1957. Her latest exhibition, Nearly Human, is about machines and objects that are nearly like us—all products of our imagination.