ARS ELECTRONICA ARCHIVE - PRIX

Der Prix Ars Electronica Showcase ist eine Sammlung, innerhalb derer die Einreichungen der KünstlerInnen zum Prix seit 1987 durchsucht und gesichtet werden können. Zu den Gewinnerprojekten liegen umfangreiche Informationen und audiovisuelle Medien vor. ALLE weiteren Einreichungen sind mit den Basisdaten in Listenform recherchierbar.

Leonardo/ISAST

Leonardo/ISAST

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_03_2568243.jpg | 2110 * 2774px | 3.7 MB | The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art, by Linda Dalrymple Henderson. Leonardo Book Series title. Revised Edition published February 2013 by The MIT Press. The long-awaited new edition of a groundbreaking work on the impact of alternative concepts of space on modern art.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_06_2568249.png | 550 * 733px | 266.1 KB | Poster for Leonardo Art Science Evening Rendezvous Los Angeles, 23 February 2017 | UCLA Art Sci center collective

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_07_2568251.png | 650 * 864px | 182.4 KB | Poster for Leonardo Art Science Evening Rendezvous Los Angeles, 17 November 2016 | UCLA Art Sci center collective

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_09_2568255.jpg | 1087 * 787px | 196.9 KB | What Does Leonardo Do Postcard | Photo credits: (left) © The Einstein Collective. Photo: Christopher O’Leary. (right) Photo: © Jon McCormack.

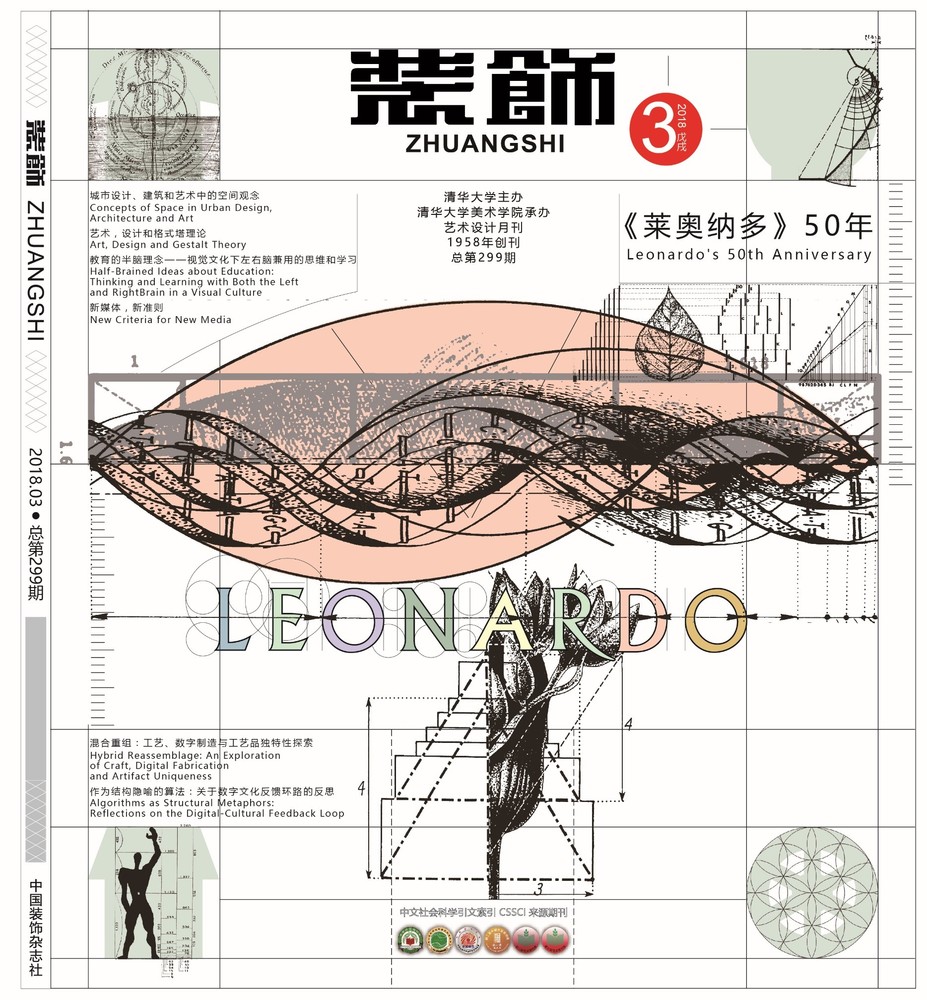

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_10_2568257.jpg | 1868 * 2015px | 846.3 KB | Cover and interior spread from Zhuangshi, the Chinese Journal of Design March 2018 issue commemorating Leonardo’s 50th anniversary. This special section translated six articles from Leonardo journal’s history. Shown is the translation of Romy Achituv “Algorithms as Structural Metaphors: Reflections on the Digital-Cultural Feedback Loop,” originally published in English in Leonardo 46, No. 2 (2013).

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_12_2568261.jpeg | 2484 * 3362px | 1.4 MB | Cover of Leonardo 1, no. 1 (January 1968).

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_13_2568265.jpeg | 2441 * 3354px | 1.8 MB | Cover of Leonardo 20, no. 4 (1987). This was the first Leonardo issue to feature an image. Cover art: Frank J. Malina, Expanding Universe, No. 1028/1966, kinetic–op art painting, fluorescent tubes, Plexiglas, acrylic paint, 80 × 60 cm, 1966.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_14_2568267.jpeg | 2550 * 3300px | 1.7 MB | Cover of Leonardo 30, no. 1 (1997). Cover art: Joseph Squier, Anatomy Frontal, altered electronic image from Polaroid original, 8 × 10 in, 1994.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_15_2568269.jpeg | 2512 * 3294px | 7.7 MB | Cover of Leonardo 40, no. 1 (2007). Cover art: Frederick Loomis, detail of Architectural Profile: Series 00:01, Edward Mathew Taylor, 2006, First Generation AXIS Technologies Class 5 Anthropomorphic Computing Platform Central Control Unit (CCU), Miriam Mosher: The Mother Platform, Circa Anno Domini 3010, colored pencil drawing on paper, 14 × 17 in, 2006. | Frederick Loomis, Courtesy Frey Norris Gallery

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_16_2568271.jpg | 2550 * 3300px | 1.2 MB | Cover of Leonardo 51, no. 3 (2018). Cover art: Krzysztof Wodiczko, Hiroshima Projection, 1999. | Krzysztof Wodiczko. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

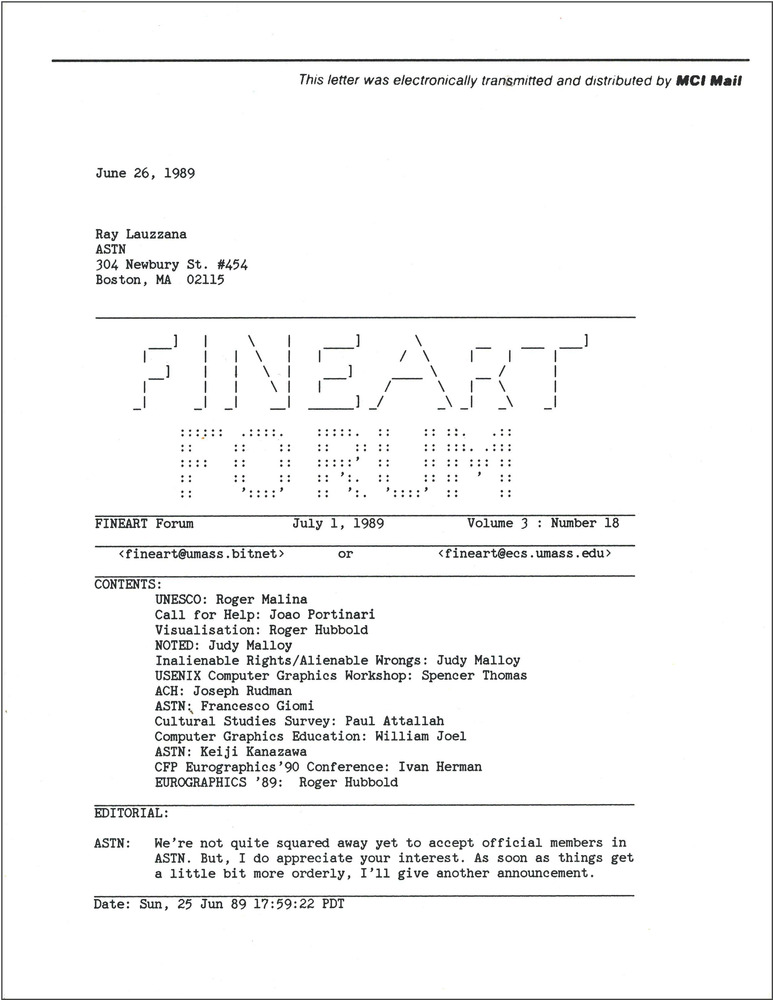

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_17_2568278.jpg | 2538 * 3284px | 998.9 KB | ISAST published, on behalf of the Art Science Technology Network (ASTN), the Fine Art Forum, one of the first (if not the first) electronic arts newsletter, over email, starting circa 1986. ISAST followed with Leonardo Electronic News starting in 1991, a precursor to the Leonardo Electronic Almanac (LEA), which launched in 1993. Ray Lauzzana was founding editor of the Fine Art Forum.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_19_2568284.jpg | 2048 * 1365px | 142.5 KB | An interactive presentation of all the front covers from Leonardo journal’s first 50 years at the 50th anniversary event organized by Rejane Spitz at PUC-Rio (Brazil), June 2017. | Images courtesy of Laboratório de Arte Eletrônica.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_20_2568286.jpg | 1068 * 712px | 105.2 KB | Nina Czegledy speaks at the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Leonardo/ISAST, during the first day of ISEA2017 at the Universidad de Caldas (Colombia). | Margarita Laverde / Press U de Caldas / June 11, 2017.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_22_2568290.jpg | 4032 * 3024px | 3.8 MB | The 2018 cohort of residents of the Scientific Delirium Madness art-science residency, a collaboration with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_23_2568292.jpg | 1350 * 797px | 194.3 KB | Jasia Reichardt spoke at the March 15 2018 DASER (DC Art Science Evening Rendezvous). After her talk, Reichardt was joined in conversation with Klaus Ottmann, deputy director for Curatorial and Academic Affairs at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. and the publisher and editor of Spring Publications.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_24_2568294.jpg | 380 * 492px | 19.7 KB | Leonardo Cover Vol 5 Nr 2 2018

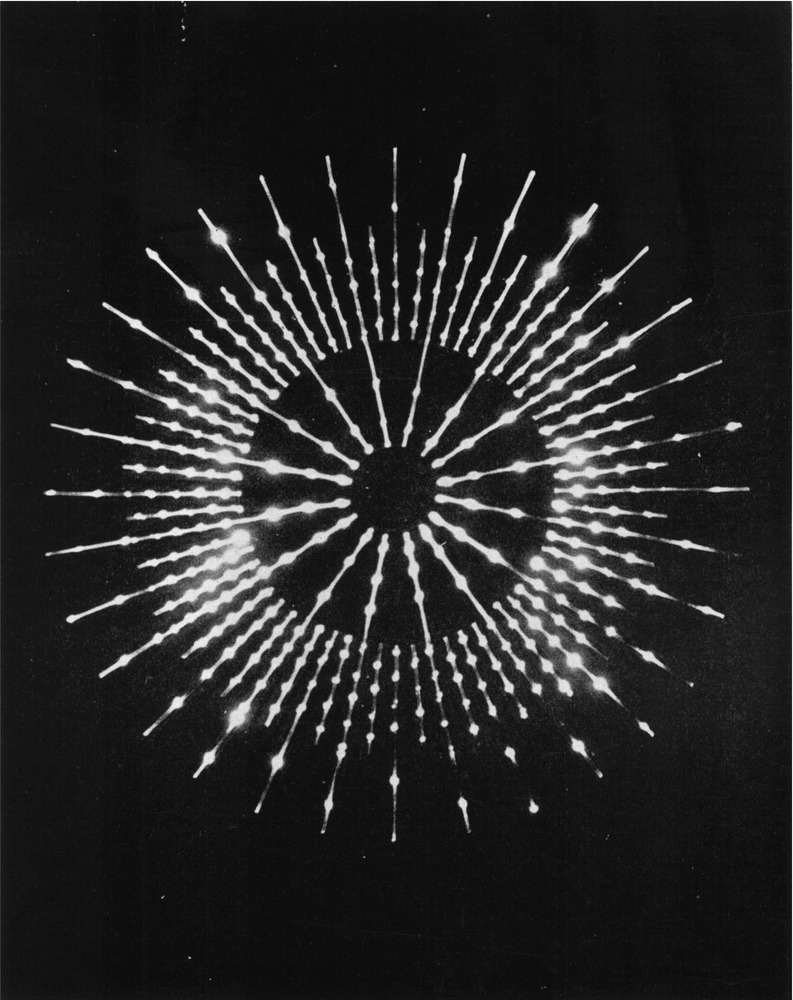

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_Leonardo_isast_kineticpainting_2568275.tiff | 1670 * 2107px | 1.8 MB | Frank J. Malina, Sink and Source, three-component lumidyne system (one Rotor), 60 × 80 cm, 1966. This image accompanied F.J. Malina’s article “Kinetic Painting: The Lumidyne System” in Leonardo 1, no. 1 (1968), pp. 25–33.

Original: VP_180001_238248_AEC_PRX_2016_leonardo_istast_FrankMalina_2568273.jpg | 1638 * 2068px | 1.5 MB | Leonardo founder Frank J. Malina standing next to a WAC Corporal missile, 1945. F.J. Malina and his fellow California Institute of Technology (Caltech) associates became known as the "Suicide Squad" because of the rocket tests they conducted while at Caltech. | NASA/JPL-Caltech

Leonardo—Coaching Global Culture

Derrick de Kerckhove

Ancient Greek scholars and etymologists are accustomed to remind us that, at the beginning, art and technology were indistinguishable in a common word tekne. Our friend Ed Shanken, a regular participant to Ars Electronica as well as to Leonardo, contributed a substantial article about the matter1. With a view to situate the role of Leonardo in the contemporary culture, it may be time to revisit this critical association and propose a hypothesis for why the separation of the two functions happened in the first place and why they are on the course of being reunited today.

The appearance of such a category as “art” is not a natural outcome of human activities generally more oriented to survival than to decorum for long stretches of evolution. Richard Wilhelm notes that Confucius was made uncomfortable when confronted with anything to do with art or esthetics. McLuhan was fond of quoting a proverb of the Balinese who were proud to claim: “We have no art, we make everything the best we can.” This mentality must have been germane to the ancient Greek sculptor or architect who did his best to develop the most efficient techniques to produce what was ordered by the Athenian authorities, including ornamentation, because gods and illustrious persons were also to be represented. It is only when a major disruption in their cognitive experience hit their culture that the technical and the artistic functions separated and revealed themselves as such to the ancient Greeks. This separation followed the invention of the alphabet, a technology that redefined their sensory experience by reducing it to a string of written words. This process permitted the discovery, the elaboration, and the promotion of common practices into new categories of knowledge and formal expertise including geometry, history, philosophy, and art.

So, why is it then, that now, overcoming a durable and contemptuous resistance from the art establishment, artists began to turn to science and technology

to produce what they still considered as art, not just technology? First of all because during and after the Renaissance, artists were often prone to adopt the latest technologies to practice their art, whether musical, pictural, sculptural, and even more so in literature. But the present paradigmatic thrust to artistic innovation is surely the development of a generalized digital culture.

Almost as soon as I took over the direction of the McLuhan Program at the University of Toronto in 1983, I created a weekly evening event entitled the “artist-engineers seminars,” an initiative squarely contemporary to the time Roger Malina took over the responsibility of continuing his father’s creation. Frank Malina’s intuition about the need for a journal both to bridge art and technology, and to add science to the mix, was a distant early warning of a social evolution that would necessarily become strengthened in the years to follow.

The hidden ground for that convergence was probably the same that has entrained convergence in all other specializations, technological, scientific, productive and distributive, that is, the shift from literate to digital dominance of human affairs. The drive to convergence was the transborder fluidity introduced by combining heterogeneous media and contents in the common simplified sequence of 0 and 1, or on/off signs that allowed to translate anything into anything else without transition in the same infrastructure of simple signs.

So the first thing to point out about the success of Leonardo, besides being a leading publication with very high academic standards addressed to a rapidly growing network of global readers and fans, accessing them also through its numerous sideline activities such as LASERs and DASERs, is that, early on, it found its place at the core of a civilizational transformation. Where the effects of literacy were centrifugal, those of digitization are centripetal forging indispensable alliances between disciplines, ushering a trans-disciplinary trend even where it is most resisted, that is, in hard sciences, neurosciences, professional turfs, etc. Leonardo is a global drive in the global culture. Its job is to infiltrate and illuminate the convergence, probing the social and human consequences of technology, thus contributing to the highest levels of cultural awareness and competences.

The penetration of Leonardo in these various bastions of protected expertise and knowledge has been relentless as it scanned and focused on the latest contemporary issues and concerns of both the culture at large and the scientific community. Roger Malina underlines this constant updating aspect of Leonardo’s work:

We have been very reactive to the evolution of activities of the professionals in the community; in the 1970s we published a lot about computer graphics before it became its own profession, but now we no longer publish about computer graphics. When the space artists started to emerge we documented and advocated their work with the space arts workshops in Paris that led to the involvement of ESA, CNES etc. and the setting up of the arts committee at the international federation of astronautics. When art and biology started emerging, Edouardo Kac and George Gessert joined the editorial board and we started documenting that work. Today it’s AI and art and complex networks, and of course the new development in the last few years is a growing interest in scientific and engineering circles of the possible role of artists and designers.2

And now Leonardo is launching a research stream in gaming. From this impressive evidence we can already observe that it is tracking artists “doing” analytics and producing algorithmic applications and installations. The opinion of artists—engineers or not—about such matters is urgent, and even more so concerning the society of “social credits” that is looming in China and that has already crept into this weird hybrid fabric of flesh and data that western societies are also adapting to.

The second point, also emphasized by Malina, is how global the network that Leonardo has created over the years is. This network of networks, as he calls it, is not merely a collective, but more likely a connective association of many different persons and organizations that all have archived identities, names, places, and connections and thus should not be lumped into the anonymous blob that people call collective. In a few decades, when scholars source the origins of the bewildering metamorphosis our human society is now traversing, their individual contributions in the journal will be recognized as prophetic.

The presence of Leonardo in the global networks is both homeopathic and viral. Over 50 years it has proven that it is here to stay. It has the continuity that reveals a function necessary at the global scale. More than a political party or even an ideology, it is a connective that functions as a guide for our evolution.

1 http://www.mediaarthistory.org/refresh/ Programmatic%20key%20texts/pdfs/Shanken.pdf

2 Adapted from a personal communication from Roger Malina.

Toward a Forest Ecology of Networked Knowledge, Innovation and Artistic Creation: Enabling New Villages of Collaboration Among Organizations and Individuals Bridging the Arts, Sciences, Engineering and Medicine

Text coordinated by Roger Malina, Nina Czegledy, Pam Grant-Ryan, Erica Hruby, Christa Sommerer, Annick Bureaud, Nick Cronbach, Christine Maxwell, Yvan Tina, and numerous others.

A Network of Networks

The Prix Ars Electronica Pioneers Award 2018 states: “The community of Leonardo is being singled out for recognition as Visionary Pioneer of Media Arts.” This is the first Nica Award to recognize a collaborative community of practice. We present here some history, ideas, and methods that have permitted a small arts organization to survive and champion the work of a growing international network of interacting artists, scientists, scholars, and curators. And yes, this network is contributing to changing the history of ideas and engaging with the hard problems. And, as in the 1970s as documented by network historian Patrick McCray, there is renewed interest among companies and startups as there was 50 years ago. We would like to take the opportunity to thank all those who have contributed with their ideas, time, work, and participation to help the Leonardo network and projects evolve. Our success comes from the volunteer contributions of editors-in-chief, authors, editorial board members, peer reviewers, advisors, project coordinators, and event hosts. These several hundred individuals have allowed more than 15,000 artists and authors to have their work documented and promoted over 50 years; we like to say that it's a larger creative community than that which fueled the Renaissance.

Key nodes are the editors-in-chief of the publications, program leaders and their institutions. These have included Michael Punt, Annick Bureaud, Sean Cubitt, Sheila Pinkel, Lanfranco Aceti, and Nic Collins, but also Piero Scaruffi and Tami Spector who triggered the Leonardo LASER network and notably the Leonardo DASER at the US National Academy of Science, led by JD Talasek. We note crucial directions initiated by first Executive Director Craig Harris, and Larry Polansky, who redirected the organization to go beyond the visual arts to include all modes of expression. Thanks also to Ray Lauzzana, Paul Brown, Judy Malloy, and Nisar Keshvani, who led Leonardo On-Line in the early days of the Web. It would be remiss to not recognize the full history of Leonardo staff, now under the leadership of Managing Director Danielle Siembieda.

Many motivations of the founding members have been realized. As the communities of practice that link the arts, sciences and emerging technologies have reached critical mass, they are now engaged on new agendas, methods, and issues. The methodology of the Leo50 birthday parties coordinated by Nina Czegledy has enabled a snapshot of the concerns of these communities of practice today. As a small nonprofit, we had no budget for this activity, so we started working with the communities of practice.

We soon realized that in spite of the tragedy of the Internet, healthy global villages can exist. As the tragedy of the commons revealed, open access has always been subject to abuse; as with the medieval commons, the invention of intentionally designed “gates” can help mitigate some of the abuse. A network of networks is one structure that can, through ethical rules of individual and group interaction, enable more positive emergent behaviors of the network as a whole. Core network science ideas have been injected by Albert-László Barabási, Max Schich, and Isabel Meirelles.

Leonardo-associated events help make the villagers visible to one another in a way that social media do not. These village gatherings are bewilderingly heterogeneous: interdisciplinary, geographically dispersed, intergenerational, of all genders and orientations. But these gatherings also make us very aware of the implicit biases introduced by the practices of academic publishing and the predominant use of the English language. This results in exclusion of much important work carried out in popular and non-institutional contexts around the world.

Looking Back to Look Forward

Continuing this “looking back, looking forward,” we acknowledge the multi-decade dedication and service of Pamela Grant-Ryan. Grant-Ryan joined the editorial staff of Leonardo journal in 1983 and held the position of managing editor from 1985 until her retirement in 2016 (Erica Hruby is now at the helm). We excerpt here the essay Grant-Ryan wrote 30 years ago to mark our twentieth anniversary:

[Founder] Frank Malina was a man who embraced change and synthesis as means to a better world.… As an aeronautical and rocket engineer pioneer, he certainly knew that change was an inevitable fact of the present and future. Yet as a humanitarian whose life experience was shaped by World War II, he was aware that scientists and engineers should not be the only ones involved in directing the changes wrought by technology; artists in particular should be instrumental in developing technology toward humane ends. “It was my feeling that one way in curbing the misuse of technology might be if we could, through the arts, emotionally prepare young people to see the aesthetic, positive side of things and also then respond by seeing the negative.” As an artist he sought to integrate his knowledge of technology and scientific working methods into his own evolving artwork. And as an editor he sought to create an interdisciplinary forum documenting synthesis and change toward the creation of a synthetic worldview.…

Trained as an engineer, [Malina] attempted to begin his artistic investigations in the usual way: to delve into the documented studies written by experts—in this case by artists. Whereas technical and scientific advancement are based on each generation of investigators building upon the exhaustively documented work that has gone before, he found to his amazement no significant relevant body of literature written by artists about their work, their methods, their discoveries or ideas. He expressed frustration that the lack of appropriate documentation in the arts caused artists to waste enormous time and energy duplicating each others’ technical discoveries. Indeed, when he began to work on his “Lumidyne” system of kinetic art, he was unable to find any precedent for kinetic painting and believed himself to be the first artist doing this type of work. When he began exhibiting his kinetic works in the mid-l950s, he learned of one artist, Thomas Wilfred, who had been producing kinetic works since 1905.

During the time Malina was discovering that artists did not have a history of, or a literary vehicle for, exchanging ideas and technical information among themselves, he began also to experience firsthand the political powerlessness of the artist. Then as now, the decision-making in the art world was in the hands of a group of non-artists, such as gallery owners, art critics, scholars and museum curators, who had assumed niches of eminence in explaining, promoting and disseminating art. By contrast, in the technical and scientific professions, documentation by the originators of the work has always appeared first, followed by explanation and comment by the popularizers, science writers and historians. Further, the decision-making in scientific research is dominated by the scientists and engineers themselves.

The establishment “supporting” the arts was at best not interested in—and at worst opposed to—innovative art such as technological or kinetic art. This kind of art was hard to analyze, hard to sell, often hard to display, and sometimes hard to repair and maintain—considerations surely not central to artistic significance. Except for a few scattered theoreticians, the individuals writing about art were engaged primarily in the business hype of selling yesterday’s ideas, since that which has already gained widespread acceptance makes for the best merchandise. Meanwhile, at a time when scientists and researchers in other disciplines were exchanging ideas and information at an ever-increasing rate, contemporary, exploratory artists seeking to extend the boundaries of art were working in relative intellectual isolation with no formal system of mutual support….

As Malina’s artistic explorations continued to evolve through various forms and media, he began to discuss the artist’s dilemma with his colleagues in both the arts and science, among them natural scientist Joseph Needham, editor Sandy Koffler, artist-teacher Vic Gray, artist and mathematician Anthony Hill, artist and scientist L. Alcopley and mathematician-artist Claude Berge. His initial idea was to form a professional society of scientist-artists in the tradition of existing scientific and technical societies, many of which publish journals as a part of their activities. Although his plans for such a society were never realized, he became ever more convinced of the need for a journal by and for artists. Malina began in the early 1960s to consider publishing a periodical modeled on scientific journals. By 1965 he had begun to contact prospective publishers and individuals to serve as editorial advisors. And in 1967 he reached an agreement with Robert Maxwell of Pergamon Press to publish the journal quarterly.... While the continued existence of Leonardo was a question of debate following the sudden death of Frank Malina in 1981, his idea, which had taken substance in the form of the journal, proved to have an importance which motivated several concerned individuals to secure its future. The editorial board framework on which the journal was based proved the key in securing its continued publication.... During 1983 and 1984 the journal found a hospitable home at San Francisco State University under the editorship of Professor Bryan Rogers [and with the leadership of Professor Steve Wilson].

For full text and references see P. Grant-Ryan, “Why Leonardo? Past, Present and Future” Leonardo 20, No. 4, 397–399 (1987). Available at www.jstor.org/stable/1578538

In 1982, Steve Wilson, with the help of colleagues including Frank Oppenheimer, set up the nonprofit International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology, which later, in tandem with the Paris-based Association Leonardo, formed two nodes that have stabilized and grown in a culture enabled by a network- of-networks design thinking. Over the decades Leonardo has collaborated with dozens of organizations and groups from ISEA, ANAT, SIGGRAPH, Arts Catalyst, US College Art Association, CIANT, The Mediterranean Institute of Advanced Studies, Telefonica Foundation, and Srishti School of Art and Design, to name but a few. Of note also is the work with Tom Linehan at ATEC, UTDallas, which, after several decades of collaboration, led to the establishment of the UTD ArtSciLab, with projects in Art- Science and experimental publishing and the housing of the executive editor of Leonardo publications.

As indicated above, the vision of the founders has in large part been realized and some of the past prejudices reversed:

“If you can plug it in, it can’t be art,” technological artists were told when they tried to exhibit their work in the 1950s and ’60s. Today the situation has almost reversed, with emerging technologies being rapidly integrated into cultural practice.

“Artists don’t write, art critics do.” At the founding it was almost impossible for artists to write about their work. Today any artists who wish to write about their work can do so through their own online publishing platforms, artists’ talks, and other methods.

“Artists don’t need Art Theory.” Today artists draw heavily on theoretical concepts from a variety of sources; the PhD in Art and Design develops art and design methods as research. Often curators become collaborators and translators bridging the points of view. Artists today are drawing on theories from computer science. Leonardo journal has benefited from the leadership of many art and science theorists and historians such as Rudolf Arnheim, Ernst Gombrich, JJ Gibson, Sundar Sarukkai, Linda Henderson, and David Carrier.

“Go show your work in New York; we show the Paris School of Art,” non- French artists in Paris were sometimes told in the early ’50s. Today, artists are geographic, institutional, and intellectual migrants.

We urge readers of this text to engage with relics of our first 50 years during the Leonardo Slam sessions at Ars Electronica, coordinated by Christa Sommerer, or to later search for its traces online. Sommerer writes:

Congratulations to 50 years of Leonardo! As an editorial board member and educator, I am particularly happy to be able to present the wonderful achievements of Leonardo to our students. These days it has become so easy to download any information from the web, to copy-paste and to mix it all up. The tremendous growth of educational programs in media art has led to a vibrant community of young media artists who are interested in building the future but also want to know about media art’s origins. What perfect timing that Leonardo comes to Linz and shows material from its 50-year history including artifacts, artworks, publications, and anecdotes. We have decided to take an unusual approach and let students, led by Benjamin Olsen and Dawn Faelnar, browse through the archive, mash it up, interpret it in a poetry slam style, and have fun by digging into these treasures. We invite everyone to participate in the Leonardo slam sessions and discover Leonardo’s glorious past and future!

And visitors of the Ars Electronica Festival 2018 can visit the Leonardo (Archive) exhibit curated by Nina Czegledy in collaboration with Christa Sommerer and Genoveva Rueckert. On the Leo50 celebrations that she chaired, Nina Czegledy writes:

Frank Malina’s life and practice remains an iconic example to the present. He perceived art as a catalyst and advocated effective interaction and a broad interpretation of knowledge transfer to achieve a harmony between the arts, sciences and technology. It is in his pioneering interdisciplinary spirit that in 2017 we initiated the Leonardo 50th Celebrations worldwide.

Early inquiries to an informal professional global network to host birthday celebrations were met with enthusiasm. As a result we have already sung Happy Birthday in many local languages from Colombia to New Zealand, Italy, South Africa—with more prospective locations on the horizon both in the US and elsewhere. The distinctive Ars Electronica Golden Nica for Visionary Pioneers of Media Art is a major inspiration to continue our efforts.

Some of our goals include: to embrace birthday parties in a variety of alternate settings; to honor interdisciplinary pioneers, Leonardo authors, editors, contributors; and very importantly to encourage the active participation of the emerging generation. All the celebratory events differ as the locally relevant content and format of each is developed and presented by the host.

While in the last decade great progress was achieved in the field of interdisciplinary education and collaborations, several issues and questions remain: How do we define today the most important elements of cross-disciplinary international collaborations? Are there any rules? How do we approach cultural differences, ethical concerns? Some of these and other issues were raised at various celebrations and, although most of the questions remain open and as of yet unresolved, the events of the past year already provided invaluable information regarding a wide variety of topics in different cultural contexts.

One of the most cherished features of the celebrations is the participation of youth: workshops for children, student presentations, performances—in short active involvement of the emerging generation in several events. The enthusiasm of Mexican students performing electroacoustic music, Canadian or Hungarian youngsters experiencing AI workshops, and Maori children deeply involved in sound workshops is something to behold! The celebrations will continue in different form and different places but in the same interdisciplinary, intergenerational, intercultural Leonardo spirit.

The Next 50 Years

As Grant-Ryan stated, the founders’ initial ideas were to form a professional society in the tradition of existing scientific and technical societies. We think this original framing is not appropriate for the emerging networked world cultures. The goal is not to create a new profession or discipline, as in the professional guilds of the middle ages and in university- created departments in later years. It is time to cut down this tree of knowledge that poses intellectual and institutional impediments to the Leonardo communities of practice.

The value of interdisciplinary thinking, long known to our networks, is gaining larger recognition. In 2013, the US National Science Foundation funded the study “Steps to an Ecology of Networked Knowledge and Innovation: Enabling New Forms of Collaboration among Sciences, Engineering, Arts, and Design.” The STEM to STEAM movement in the United States had begun to engage with other sectors of society outside of the art, science, and technology communities. There are global initiatives such as the U.K.’s Wellcome Trust. The EU’s STARTS funding program, and the US national academies now recognize this critical mass of activity and its growing relevance to societal concerns.

We embark on the next 50 years by listening to our community and working together to redesign our future. Many challenges remain, as we heard at the birthday parties:

1. Most of the professionals in the Leonardo networks carry out their work enabled by close collaboration with others. Yet our universities insist on giving diplomas to individuals rather than groups. The Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica awarded to a collective is indicative of the new direction. Yes, we need amazing professionals like da Vinci, but we also need groups that behave with genius-like originality and impact and are rewarded for doing so. Places like Ars Electronica are breeding grounds for the new Leonardos.

2. The implicit biases of our communities are deep and intractable. If we analyze the 15,000 professionals who have made their work visible through Leonardo methods, we reluctantly admit that we have failed in part in the vision of the founders. The artists and authors are predominantly from the Western hemisphere and from traditional institutions and, yes, predominantly male. The Leonardo Virtual Africa project, relaunched under Yvan Tina, has been engaging the African and diaspora community for 20 years, as has Ars Electronica. We have begun publishing multilingually, with podcasts and texts in 15 languages on our new collaboration platform arteca. mit.edu. Recently a Leo50 birthday party was held at the Women in Art, Science and Technology meeting in Portugal, initiated by Marta de Menezes. The convening drew 70 international intergenerational women artists and drove home that it is indeed possible to create global villages.

3. How do we rethink the commercial embedding of our work? The whole structure of museums, art fairs and collectors, largely invented in the nineteenth century and adapted in minor ways to address digital culture, is incompatible with hybrid, evolving, and often not static or object-based practices. The early interest of foundations such as the Rockefeller, Mellon and Keck Foundations, more recently the Carasso Foundation, and the innovative CERN residency programs, is however indicative of new trends. Tied to this is the need to reinvent notions of intellectual property in transdisciplinary and trans-professional work.

4. A notable feature of the Leonardo gatherings is their intergenerational nature. The recent Leonardo Book Sprint in Manizales, Colombia, the upcoming Leonardo 50th Convening in San Francisco, and the Leonardo Slam at Ars Electronica are attempts to change the context and the source of ideas. Through the Leonardo Abstracts Service database, the works of new matriculates of university graduate programs are recognized and made visible. Our Creative Disturbance podcast platform is open to emerging professionals over the planet, with a number of international students receiving awards obtained through a Leonardo Kickstarter campaign. The vibrant maker, hacker, fablab, and coworking communities are highly reactive in ways that larger organizations cannot be and work in ways often incompatible with academic publishing. How do we conquer impedances?

5. How do we make real the network-of-networks metaphor? How can small organizations using network science and technologies work together differently to help make the network robust, ethical, and constructively disruptive as it grows?

6. How do we couple with dominant organizations in our society without buying into ideas and principles we don’t always agree with? 50 years ago there were no institutional programs where the Leonardo networks creative community could get formal training, never mind be employed. Most hybrids did their work totally hidden from their main profession. Now we have graduate education spreading, including PhDs, in Art and Technology and Art and Science. The good news is that emerging professionals can actually have careers. Companies are hiring MFAs in Art and Design. The bad news is that we are engaged in deep struggles with these institutions because often their institutional goals and methods are incompatible with transdisciplinary, non discipline based, approaches.

In closing, the collective authors note: Leonardo and Ars Electronica are but two nodes in this developing 21st-century work. We would like to thank Hannes Leopoldseder, Herbert W. Franke, and their comrades for their persistence in creating Ars Electronica 40 years ago, Christine Schöpf and Peter Weibel for their key contributions, and to Gerfried Stocker for a steady hand piloting through chaos, but also for their determination to cross-connect and engage in constructive coopetition with organizations such as Leonardo and numerous others to build an interconnected set of communities of practice. Cut down the Tree; we need forests and ecologies of knowledge that can mutualize in the face of climate change and the other problems of our time.

Collaboration Acknowledgments: As we have insisted, the Leonardo organizations have only succeeded because of the voluntary and dedicated contributions of hundreds of individuals. Inevitably in this text we have omitted many names of people who had crucial roles, and we apologize in advance for not naming them here. As we have also stated, yes, we need individual geniuses like Da Vinci, but we also need groups of people who behave with genius; alas, we do not yet have viable 21st systems for attribution and IP.

Derrick de Kerckhove

Ancient Greek scholars and etymologists are accustomed to remind us that, at the beginning, art and technology were indistinguishable in a common word tekne. Our friend Ed Shanken, a regular participant to Ars Electronica as well as to Leonardo, contributed a substantial article about the matter1. With a view to situate the role of Leonardo in the contemporary culture, it may be time to revisit this critical association and propose a hypothesis for why the separation of the two functions happened in the first place and why they are on the course of being reunited today.

The appearance of such a category as “art” is not a natural outcome of human activities generally more oriented to survival than to decorum for long stretches of evolution. Richard Wilhelm notes that Confucius was made uncomfortable when confronted with anything to do with art or esthetics. McLuhan was fond of quoting a proverb of the Balinese who were proud to claim: “We have no art, we make everything the best we can.” This mentality must have been germane to the ancient Greek sculptor or architect who did his best to develop the most efficient techniques to produce what was ordered by the Athenian authorities, including ornamentation, because gods and illustrious persons were also to be represented. It is only when a major disruption in their cognitive experience hit their culture that the technical and the artistic functions separated and revealed themselves as such to the ancient Greeks. This separation followed the invention of the alphabet, a technology that redefined their sensory experience by reducing it to a string of written words. This process permitted the discovery, the elaboration, and the promotion of common practices into new categories of knowledge and formal expertise including geometry, history, philosophy, and art.

So, why is it then, that now, overcoming a durable and contemptuous resistance from the art establishment, artists began to turn to science and technology

to produce what they still considered as art, not just technology? First of all because during and after the Renaissance, artists were often prone to adopt the latest technologies to practice their art, whether musical, pictural, sculptural, and even more so in literature. But the present paradigmatic thrust to artistic innovation is surely the development of a generalized digital culture.

Almost as soon as I took over the direction of the McLuhan Program at the University of Toronto in 1983, I created a weekly evening event entitled the “artist-engineers seminars,” an initiative squarely contemporary to the time Roger Malina took over the responsibility of continuing his father’s creation. Frank Malina’s intuition about the need for a journal both to bridge art and technology, and to add science to the mix, was a distant early warning of a social evolution that would necessarily become strengthened in the years to follow.

The hidden ground for that convergence was probably the same that has entrained convergence in all other specializations, technological, scientific, productive and distributive, that is, the shift from literate to digital dominance of human affairs. The drive to convergence was the transborder fluidity introduced by combining heterogeneous media and contents in the common simplified sequence of 0 and 1, or on/off signs that allowed to translate anything into anything else without transition in the same infrastructure of simple signs.

So the first thing to point out about the success of Leonardo, besides being a leading publication with very high academic standards addressed to a rapidly growing network of global readers and fans, accessing them also through its numerous sideline activities such as LASERs and DASERs, is that, early on, it found its place at the core of a civilizational transformation. Where the effects of literacy were centrifugal, those of digitization are centripetal forging indispensable alliances between disciplines, ushering a trans-disciplinary trend even where it is most resisted, that is, in hard sciences, neurosciences, professional turfs, etc. Leonardo is a global drive in the global culture. Its job is to infiltrate and illuminate the convergence, probing the social and human consequences of technology, thus contributing to the highest levels of cultural awareness and competences.

The penetration of Leonardo in these various bastions of protected expertise and knowledge has been relentless as it scanned and focused on the latest contemporary issues and concerns of both the culture at large and the scientific community. Roger Malina underlines this constant updating aspect of Leonardo’s work:

We have been very reactive to the evolution of activities of the professionals in the community; in the 1970s we published a lot about computer graphics before it became its own profession, but now we no longer publish about computer graphics. When the space artists started to emerge we documented and advocated their work with the space arts workshops in Paris that led to the involvement of ESA, CNES etc. and the setting up of the arts committee at the international federation of astronautics. When art and biology started emerging, Edouardo Kac and George Gessert joined the editorial board and we started documenting that work. Today it’s AI and art and complex networks, and of course the new development in the last few years is a growing interest in scientific and engineering circles of the possible role of artists and designers.2

And now Leonardo is launching a research stream in gaming. From this impressive evidence we can already observe that it is tracking artists “doing” analytics and producing algorithmic applications and installations. The opinion of artists—engineers or not—about such matters is urgent, and even more so concerning the society of “social credits” that is looming in China and that has already crept into this weird hybrid fabric of flesh and data that western societies are also adapting to.

The second point, also emphasized by Malina, is how global the network that Leonardo has created over the years is. This network of networks, as he calls it, is not merely a collective, but more likely a connective association of many different persons and organizations that all have archived identities, names, places, and connections and thus should not be lumped into the anonymous blob that people call collective. In a few decades, when scholars source the origins of the bewildering metamorphosis our human society is now traversing, their individual contributions in the journal will be recognized as prophetic.

The presence of Leonardo in the global networks is both homeopathic and viral. Over 50 years it has proven that it is here to stay. It has the continuity that reveals a function necessary at the global scale. More than a political party or even an ideology, it is a connective that functions as a guide for our evolution.

1 http://www.mediaarthistory.org/refresh/ Programmatic%20key%20texts/pdfs/Shanken.pdf

2 Adapted from a personal communication from Roger Malina.

Toward a Forest Ecology of Networked Knowledge, Innovation and Artistic Creation: Enabling New Villages of Collaboration Among Organizations and Individuals Bridging the Arts, Sciences, Engineering and Medicine

Text coordinated by Roger Malina, Nina Czegledy, Pam Grant-Ryan, Erica Hruby, Christa Sommerer, Annick Bureaud, Nick Cronbach, Christine Maxwell, Yvan Tina, and numerous others.

A Network of Networks

The Prix Ars Electronica Pioneers Award 2018 states: “The community of Leonardo is being singled out for recognition as Visionary Pioneer of Media Arts.” This is the first Nica Award to recognize a collaborative community of practice. We present here some history, ideas, and methods that have permitted a small arts organization to survive and champion the work of a growing international network of interacting artists, scientists, scholars, and curators. And yes, this network is contributing to changing the history of ideas and engaging with the hard problems. And, as in the 1970s as documented by network historian Patrick McCray, there is renewed interest among companies and startups as there was 50 years ago. We would like to take the opportunity to thank all those who have contributed with their ideas, time, work, and participation to help the Leonardo network and projects evolve. Our success comes from the volunteer contributions of editors-in-chief, authors, editorial board members, peer reviewers, advisors, project coordinators, and event hosts. These several hundred individuals have allowed more than 15,000 artists and authors to have their work documented and promoted over 50 years; we like to say that it's a larger creative community than that which fueled the Renaissance.

Key nodes are the editors-in-chief of the publications, program leaders and their institutions. These have included Michael Punt, Annick Bureaud, Sean Cubitt, Sheila Pinkel, Lanfranco Aceti, and Nic Collins, but also Piero Scaruffi and Tami Spector who triggered the Leonardo LASER network and notably the Leonardo DASER at the US National Academy of Science, led by JD Talasek. We note crucial directions initiated by first Executive Director Craig Harris, and Larry Polansky, who redirected the organization to go beyond the visual arts to include all modes of expression. Thanks also to Ray Lauzzana, Paul Brown, Judy Malloy, and Nisar Keshvani, who led Leonardo On-Line in the early days of the Web. It would be remiss to not recognize the full history of Leonardo staff, now under the leadership of Managing Director Danielle Siembieda.

Many motivations of the founding members have been realized. As the communities of practice that link the arts, sciences and emerging technologies have reached critical mass, they are now engaged on new agendas, methods, and issues. The methodology of the Leo50 birthday parties coordinated by Nina Czegledy has enabled a snapshot of the concerns of these communities of practice today. As a small nonprofit, we had no budget for this activity, so we started working with the communities of practice.

We soon realized that in spite of the tragedy of the Internet, healthy global villages can exist. As the tragedy of the commons revealed, open access has always been subject to abuse; as with the medieval commons, the invention of intentionally designed “gates” can help mitigate some of the abuse. A network of networks is one structure that can, through ethical rules of individual and group interaction, enable more positive emergent behaviors of the network as a whole. Core network science ideas have been injected by Albert-László Barabási, Max Schich, and Isabel Meirelles.

Leonardo-associated events help make the villagers visible to one another in a way that social media do not. These village gatherings are bewilderingly heterogeneous: interdisciplinary, geographically dispersed, intergenerational, of all genders and orientations. But these gatherings also make us very aware of the implicit biases introduced by the practices of academic publishing and the predominant use of the English language. This results in exclusion of much important work carried out in popular and non-institutional contexts around the world.

Looking Back to Look Forward

Continuing this “looking back, looking forward,” we acknowledge the multi-decade dedication and service of Pamela Grant-Ryan. Grant-Ryan joined the editorial staff of Leonardo journal in 1983 and held the position of managing editor from 1985 until her retirement in 2016 (Erica Hruby is now at the helm). We excerpt here the essay Grant-Ryan wrote 30 years ago to mark our twentieth anniversary:

[Founder] Frank Malina was a man who embraced change and synthesis as means to a better world.… As an aeronautical and rocket engineer pioneer, he certainly knew that change was an inevitable fact of the present and future. Yet as a humanitarian whose life experience was shaped by World War II, he was aware that scientists and engineers should not be the only ones involved in directing the changes wrought by technology; artists in particular should be instrumental in developing technology toward humane ends. “It was my feeling that one way in curbing the misuse of technology might be if we could, through the arts, emotionally prepare young people to see the aesthetic, positive side of things and also then respond by seeing the negative.” As an artist he sought to integrate his knowledge of technology and scientific working methods into his own evolving artwork. And as an editor he sought to create an interdisciplinary forum documenting synthesis and change toward the creation of a synthetic worldview.…

Trained as an engineer, [Malina] attempted to begin his artistic investigations in the usual way: to delve into the documented studies written by experts—in this case by artists. Whereas technical and scientific advancement are based on each generation of investigators building upon the exhaustively documented work that has gone before, he found to his amazement no significant relevant body of literature written by artists about their work, their methods, their discoveries or ideas. He expressed frustration that the lack of appropriate documentation in the arts caused artists to waste enormous time and energy duplicating each others’ technical discoveries. Indeed, when he began to work on his “Lumidyne” system of kinetic art, he was unable to find any precedent for kinetic painting and believed himself to be the first artist doing this type of work. When he began exhibiting his kinetic works in the mid-l950s, he learned of one artist, Thomas Wilfred, who had been producing kinetic works since 1905.

During the time Malina was discovering that artists did not have a history of, or a literary vehicle for, exchanging ideas and technical information among themselves, he began also to experience firsthand the political powerlessness of the artist. Then as now, the decision-making in the art world was in the hands of a group of non-artists, such as gallery owners, art critics, scholars and museum curators, who had assumed niches of eminence in explaining, promoting and disseminating art. By contrast, in the technical and scientific professions, documentation by the originators of the work has always appeared first, followed by explanation and comment by the popularizers, science writers and historians. Further, the decision-making in scientific research is dominated by the scientists and engineers themselves.

The establishment “supporting” the arts was at best not interested in—and at worst opposed to—innovative art such as technological or kinetic art. This kind of art was hard to analyze, hard to sell, often hard to display, and sometimes hard to repair and maintain—considerations surely not central to artistic significance. Except for a few scattered theoreticians, the individuals writing about art were engaged primarily in the business hype of selling yesterday’s ideas, since that which has already gained widespread acceptance makes for the best merchandise. Meanwhile, at a time when scientists and researchers in other disciplines were exchanging ideas and information at an ever-increasing rate, contemporary, exploratory artists seeking to extend the boundaries of art were working in relative intellectual isolation with no formal system of mutual support….

As Malina’s artistic explorations continued to evolve through various forms and media, he began to discuss the artist’s dilemma with his colleagues in both the arts and science, among them natural scientist Joseph Needham, editor Sandy Koffler, artist-teacher Vic Gray, artist and mathematician Anthony Hill, artist and scientist L. Alcopley and mathematician-artist Claude Berge. His initial idea was to form a professional society of scientist-artists in the tradition of existing scientific and technical societies, many of which publish journals as a part of their activities. Although his plans for such a society were never realized, he became ever more convinced of the need for a journal by and for artists. Malina began in the early 1960s to consider publishing a periodical modeled on scientific journals. By 1965 he had begun to contact prospective publishers and individuals to serve as editorial advisors. And in 1967 he reached an agreement with Robert Maxwell of Pergamon Press to publish the journal quarterly.... While the continued existence of Leonardo was a question of debate following the sudden death of Frank Malina in 1981, his idea, which had taken substance in the form of the journal, proved to have an importance which motivated several concerned individuals to secure its future. The editorial board framework on which the journal was based proved the key in securing its continued publication.... During 1983 and 1984 the journal found a hospitable home at San Francisco State University under the editorship of Professor Bryan Rogers [and with the leadership of Professor Steve Wilson].

For full text and references see P. Grant-Ryan, “Why Leonardo? Past, Present and Future” Leonardo 20, No. 4, 397–399 (1987). Available at www.jstor.org/stable/1578538

In 1982, Steve Wilson, with the help of colleagues including Frank Oppenheimer, set up the nonprofit International Society for the Arts, Sciences and Technology, which later, in tandem with the Paris-based Association Leonardo, formed two nodes that have stabilized and grown in a culture enabled by a network- of-networks design thinking. Over the decades Leonardo has collaborated with dozens of organizations and groups from ISEA, ANAT, SIGGRAPH, Arts Catalyst, US College Art Association, CIANT, The Mediterranean Institute of Advanced Studies, Telefonica Foundation, and Srishti School of Art and Design, to name but a few. Of note also is the work with Tom Linehan at ATEC, UTDallas, which, after several decades of collaboration, led to the establishment of the UTD ArtSciLab, with projects in Art- Science and experimental publishing and the housing of the executive editor of Leonardo publications.

As indicated above, the vision of the founders has in large part been realized and some of the past prejudices reversed:

“If you can plug it in, it can’t be art,” technological artists were told when they tried to exhibit their work in the 1950s and ’60s. Today the situation has almost reversed, with emerging technologies being rapidly integrated into cultural practice.

“Artists don’t write, art critics do.” At the founding it was almost impossible for artists to write about their work. Today any artists who wish to write about their work can do so through their own online publishing platforms, artists’ talks, and other methods.

“Artists don’t need Art Theory.” Today artists draw heavily on theoretical concepts from a variety of sources; the PhD in Art and Design develops art and design methods as research. Often curators become collaborators and translators bridging the points of view. Artists today are drawing on theories from computer science. Leonardo journal has benefited from the leadership of many art and science theorists and historians such as Rudolf Arnheim, Ernst Gombrich, JJ Gibson, Sundar Sarukkai, Linda Henderson, and David Carrier.

“Go show your work in New York; we show the Paris School of Art,” non- French artists in Paris were sometimes told in the early ’50s. Today, artists are geographic, institutional, and intellectual migrants.

We urge readers of this text to engage with relics of our first 50 years during the Leonardo Slam sessions at Ars Electronica, coordinated by Christa Sommerer, or to later search for its traces online. Sommerer writes:

Congratulations to 50 years of Leonardo! As an editorial board member and educator, I am particularly happy to be able to present the wonderful achievements of Leonardo to our students. These days it has become so easy to download any information from the web, to copy-paste and to mix it all up. The tremendous growth of educational programs in media art has led to a vibrant community of young media artists who are interested in building the future but also want to know about media art’s origins. What perfect timing that Leonardo comes to Linz and shows material from its 50-year history including artifacts, artworks, publications, and anecdotes. We have decided to take an unusual approach and let students, led by Benjamin Olsen and Dawn Faelnar, browse through the archive, mash it up, interpret it in a poetry slam style, and have fun by digging into these treasures. We invite everyone to participate in the Leonardo slam sessions and discover Leonardo’s glorious past and future!

And visitors of the Ars Electronica Festival 2018 can visit the Leonardo (Archive) exhibit curated by Nina Czegledy in collaboration with Christa Sommerer and Genoveva Rueckert. On the Leo50 celebrations that she chaired, Nina Czegledy writes:

Frank Malina’s life and practice remains an iconic example to the present. He perceived art as a catalyst and advocated effective interaction and a broad interpretation of knowledge transfer to achieve a harmony between the arts, sciences and technology. It is in his pioneering interdisciplinary spirit that in 2017 we initiated the Leonardo 50th Celebrations worldwide.

Early inquiries to an informal professional global network to host birthday celebrations were met with enthusiasm. As a result we have already sung Happy Birthday in many local languages from Colombia to New Zealand, Italy, South Africa—with more prospective locations on the horizon both in the US and elsewhere. The distinctive Ars Electronica Golden Nica for Visionary Pioneers of Media Art is a major inspiration to continue our efforts.

Some of our goals include: to embrace birthday parties in a variety of alternate settings; to honor interdisciplinary pioneers, Leonardo authors, editors, contributors; and very importantly to encourage the active participation of the emerging generation. All the celebratory events differ as the locally relevant content and format of each is developed and presented by the host.

While in the last decade great progress was achieved in the field of interdisciplinary education and collaborations, several issues and questions remain: How do we define today the most important elements of cross-disciplinary international collaborations? Are there any rules? How do we approach cultural differences, ethical concerns? Some of these and other issues were raised at various celebrations and, although most of the questions remain open and as of yet unresolved, the events of the past year already provided invaluable information regarding a wide variety of topics in different cultural contexts.

One of the most cherished features of the celebrations is the participation of youth: workshops for children, student presentations, performances—in short active involvement of the emerging generation in several events. The enthusiasm of Mexican students performing electroacoustic music, Canadian or Hungarian youngsters experiencing AI workshops, and Maori children deeply involved in sound workshops is something to behold! The celebrations will continue in different form and different places but in the same interdisciplinary, intergenerational, intercultural Leonardo spirit.

The Next 50 Years

As Grant-Ryan stated, the founders’ initial ideas were to form a professional society in the tradition of existing scientific and technical societies. We think this original framing is not appropriate for the emerging networked world cultures. The goal is not to create a new profession or discipline, as in the professional guilds of the middle ages and in university- created departments in later years. It is time to cut down this tree of knowledge that poses intellectual and institutional impediments to the Leonardo communities of practice.

The value of interdisciplinary thinking, long known to our networks, is gaining larger recognition. In 2013, the US National Science Foundation funded the study “Steps to an Ecology of Networked Knowledge and Innovation: Enabling New Forms of Collaboration among Sciences, Engineering, Arts, and Design.” The STEM to STEAM movement in the United States had begun to engage with other sectors of society outside of the art, science, and technology communities. There are global initiatives such as the U.K.’s Wellcome Trust. The EU’s STARTS funding program, and the US national academies now recognize this critical mass of activity and its growing relevance to societal concerns.

We embark on the next 50 years by listening to our community and working together to redesign our future. Many challenges remain, as we heard at the birthday parties:

1. Most of the professionals in the Leonardo networks carry out their work enabled by close collaboration with others. Yet our universities insist on giving diplomas to individuals rather than groups. The Prix Ars Electronica Golden Nica awarded to a collective is indicative of the new direction. Yes, we need amazing professionals like da Vinci, but we also need groups that behave with genius-like originality and impact and are rewarded for doing so. Places like Ars Electronica are breeding grounds for the new Leonardos.

2. The implicit biases of our communities are deep and intractable. If we analyze the 15,000 professionals who have made their work visible through Leonardo methods, we reluctantly admit that we have failed in part in the vision of the founders. The artists and authors are predominantly from the Western hemisphere and from traditional institutions and, yes, predominantly male. The Leonardo Virtual Africa project, relaunched under Yvan Tina, has been engaging the African and diaspora community for 20 years, as has Ars Electronica. We have begun publishing multilingually, with podcasts and texts in 15 languages on our new collaboration platform arteca. mit.edu. Recently a Leo50 birthday party was held at the Women in Art, Science and Technology meeting in Portugal, initiated by Marta de Menezes. The convening drew 70 international intergenerational women artists and drove home that it is indeed possible to create global villages.

3. How do we rethink the commercial embedding of our work? The whole structure of museums, art fairs and collectors, largely invented in the nineteenth century and adapted in minor ways to address digital culture, is incompatible with hybrid, evolving, and often not static or object-based practices. The early interest of foundations such as the Rockefeller, Mellon and Keck Foundations, more recently the Carasso Foundation, and the innovative CERN residency programs, is however indicative of new trends. Tied to this is the need to reinvent notions of intellectual property in transdisciplinary and trans-professional work.

4. A notable feature of the Leonardo gatherings is their intergenerational nature. The recent Leonardo Book Sprint in Manizales, Colombia, the upcoming Leonardo 50th Convening in San Francisco, and the Leonardo Slam at Ars Electronica are attempts to change the context and the source of ideas. Through the Leonardo Abstracts Service database, the works of new matriculates of university graduate programs are recognized and made visible. Our Creative Disturbance podcast platform is open to emerging professionals over the planet, with a number of international students receiving awards obtained through a Leonardo Kickstarter campaign. The vibrant maker, hacker, fablab, and coworking communities are highly reactive in ways that larger organizations cannot be and work in ways often incompatible with academic publishing. How do we conquer impedances?

5. How do we make real the network-of-networks metaphor? How can small organizations using network science and technologies work together differently to help make the network robust, ethical, and constructively disruptive as it grows?

6. How do we couple with dominant organizations in our society without buying into ideas and principles we don’t always agree with? 50 years ago there were no institutional programs where the Leonardo networks creative community could get formal training, never mind be employed. Most hybrids did their work totally hidden from their main profession. Now we have graduate education spreading, including PhDs, in Art and Technology and Art and Science. The good news is that emerging professionals can actually have careers. Companies are hiring MFAs in Art and Design. The bad news is that we are engaged in deep struggles with these institutions because often their institutional goals and methods are incompatible with transdisciplinary, non discipline based, approaches.

In closing, the collective authors note: Leonardo and Ars Electronica are but two nodes in this developing 21st-century work. We would like to thank Hannes Leopoldseder, Herbert W. Franke, and their comrades for their persistence in creating Ars Electronica 40 years ago, Christine Schöpf and Peter Weibel for their key contributions, and to Gerfried Stocker for a steady hand piloting through chaos, but also for their determination to cross-connect and engage in constructive coopetition with organizations such as Leonardo and numerous others to build an interconnected set of communities of practice. Cut down the Tree; we need forests and ecologies of knowledge that can mutualize in the face of climate change and the other problems of our time.

Collaboration Acknowledgments: As we have insisted, the Leonardo organizations have only succeeded because of the voluntary and dedicated contributions of hundreds of individuals. Inevitably in this text we have omitted many names of people who had crucial roles, and we apologize in advance for not naming them here. As we have also stated, yes, we need individual geniuses like Da Vinci, but we also need groups of people who behave with genius; alas, we do not yet have viable 21st systems for attribution and IP.